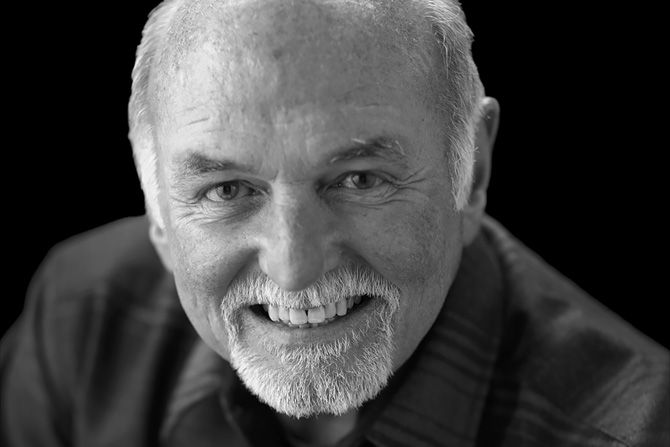

In this edition, we continue our interviews with local architectural legends. We spoke with retired GSBS Principal, Stephen Smith about his life, education and career.

When did you decide to become an architect?

I was going to be a history professor and got my bachelor honors degree in history at the U. I was headed for graduate school to become a Ph.D. history professor. I graduated in 1968. They did away with graduate deferments: (I was) eligible for the draft, advanced infantry training, and Vietnam. It was a path I was not interested in.

I got into the Navy Officer Candidate School, where you had to volunteer to go to Vietnam. I volunteered for a refrigerator ship out of Newport, Rhode Island, and I got sent to Vietnam, one of the first three non-volunteers they sent. In the Navy, I realized that I was interested in a lot of things: art, science, people, politics. I thought, what can I do that covers the broadest range of interests? What about architecture? It has an art component, a technical component, a political component, and a social component that deals with people at every level. Maybe I’ll try that.

I got out of the Navy and didn’t know anything about architecture because when you went to school in the sixties, you didn’t take classes like physics and calculus and all the prerequisites for architecture. You wouldn’t have anything to do with a slide rule. It was all existential poetry and sociology and politically relevant things. I had to do an extra year of school to be eligible for architecture school.

When I started, I didn’t know what a section drawing was. I didn’t know what an elevation drawing was. Fortunately, the year I was taking all the prerequisites, a professor of architecture agreed to do a reading program with me, and I read a book every week that he told me to read, and then we’d spend two or three hours talking about it. All volunteer on his part. It was a great way to become familiar with architecture in a broader sense.

I started school in January, as I got out of the Navy at the end of December, so I was off-sequence. I took basic design and a 15-hour course credit in the summer, three-quarters of school in one session. It was quite intense.

Architecture school is a lot of work, long hours. In hindsight, I probably learned a lot more from my fellow students than I did from the faculty. There were some faculty people who were very helpful and some who were pretty much not helpful. We had a good class of talented people, and we worked together quite well, solving most of the problems given to us by the faculty. And we challenged the faculty. For example, we had a restaurant project assigned to us. We interviewed all these people who owned restaurants, cooked in, and worked in restaurants to see what they were like. We were actually reprimanded for doing that because we weren’t doing it by the rules. We insisted on having restaurant people on the jury, and they invited a couple of restaurant guys to sit in.

It was a very interesting education in that it was not only technical and not only developed the skills you needed to work in architecture but also developed camaraderie and group relationships, which served us well in practice.

You graduated when?

In 1975. I graduated from the U with a master’s degree. At the time, there were limited jobs. I applied and was accepted to do the Historic American Building Survey through the National Park Service for a summer, which gave me four months to look for work. I was married, had a young toddler daughter, and needed a job. Not only was it a great experience, but it also bought me time. Then I went to work for John Clawson for a few months and then Carpenter Stringham for a few years, and then Brixen and Christopher for quite a while, and Edwards and Daniels.

Talk about what you learned in each office.

I had worked with John Clawson for a summer when I was in school. His was a small practice, and it was good because I got a lot of exposure to engineering consultants and clients that you might not get in larger firms when you are right out of school. Unfortunately, he didn’t have a growth pattern, and we didn’t develop a lot of work. One Friday, he said, “I don’t have anything for you guys to do,” and Monday morning, I went out and got a new job at Carpenter and Stringham. That was a good place to work for a while. I got my license while I was there. I passed all the exams. I had some good experiences technically there. But one weekend, I decided there wasn’t a future there.

So, I called Jim Christopher and he hired me. I worked there for several years, and that was an excellent experience. They were very good architects, and I actually did some of my best work there. The preservation development strategies did when I was on the Heritage Foundation was superb stuff. But I didn’t sense a future there either. They were not developing a culture of growth with younger people, and I went to Edwards and Daniels and had a similar experience there.

When Abe Gillis and Bob Brotherton started Gillies Brotherton in 1978, I asked Abe, “I want to come work for you,” and he said, “No, I like you as my friend. We were neighbors. Maybe someday.” In 1986, Abe called me and said, “We’re talking with David Brems about bringing him in and forming a firm with a broader practice. Now I would like you to join me as my partner.”

Bingo. Yeah, that’s what I wanted to do.

Mike and Abe had a very strong practice in industrial and some institutional work. David had a portfolio with private development, and I had some good planning experience. We thought that was a good, healthy merger of broader market areas and personality. We’re very different people, and it turned out to be a very positive group in spite of our idiosyncrasies.

The first thing I did was manage the Consolidated Maintenance Facility project at Tooele Army Depot. I had only been with them a week or so before the interview. That was a significant project because of the environmental issues associated with it. It had zero discharge of pollutants, even though it was cleaning engine parts and doing a lot of nasty processes. We had a very sophisticated roof with skylights over the eight-acre shop floor. In the interior, there was daylight on the work floor with no glare. Pretty significant impact from an environmental perspective, long before anybody talked about LEED or anything else.

From there, I moved into some planning work. We did the Judicial System Master Plan for the State of Utah and State of Utah Library Studies. I led the teams on both of those. We developed a lot of work based on the judicial master plan and subsequent court remodeling and established a relationship with the Office of the Courts. That expanded our ability to work for the State of Utah on a wide variety of projects, not only buildings but also planning and helping solve their problems.

The library study, for example, was when all the colleges and institutions in Utah had the worst libraries in the state. All I had to do was ask them. They wanted a pile of money that was way out of reach of the legislature. The legislature said, “Wait a minute, you guys all can’t have the worst. Somebody has got to be worst.”

We were hired to sort through that and were able to do it quite effectively. We had some good consultants and visited all the facilities. We could say, “Do you realize that such and such school does not even have a library? Wouldn’t they be in worse shape than you?” We were able to come to a unanimous decision of all the university and college presidents in a priority order of which libraries needed the first attention.

We worked through that list in a way that’s pretty remarkable with all those egos and institutions. All of those projects were realized in the order that we established. They had a budget that was a fraction of their demands. That established our credibility, which led to the Open Space Plan, the Salt Lake City Zoning Ordinance, and some of the other things we did that weren’t traditional architectural project stuff.

Which projects give you the most satisfaction?

There are various ways to look at it. We did the addition to the Cazier Library at Utah State University; it turned out to be a very successful project. When I see the impact of that building on the users and the hundreds and hundreds of students that go through USU and have a positive experience with that building, that’s very satisfying. Then there’s the planning work like the Open Space Plan for Salt Lake City and the Preservation Development Strategies, which have had a long-lasting impact on the community of Salt Lake.

Any disappointments?

There are the projects you’ve wanted and were thoroughly invested in and pursued for years, and you don’t get them, such as the State Courts Building. We worked for years with that goal in mind, and we didn’t get it.

There are also disappointments in some of the construction and people you work with. I was involved in most of the hiring for GSBS. I think I did a pretty good job developing and creating a culture and environment of people who were effective in defining GSBS. But occasionally you miss, and it is disappointing when you feel like you’re investing a lot of emotion in a young person’s career development, and it doesn’t work. But when it works, it’s fabulous.

People say, how did you decide to retire? For me, it got to a point where I could say to myself, all right, I’ve had some reasonably good success in the profession, and I could say I hired well, I mentored well. It’s time to get out of the way. When that hit me, it was time to get out of the way. It was an easy decision.

What changes did you see in the industry?

When we were in school, they talked about these architects as these individuals. We had a book we had to read called The Master Builders by Peter Blake. The master builders were Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies Van Der Rohe and Le Corbusier. The book treated these guys as heroes. Well, architects don’t build anything. Construction people build stuff. These guys weren’t master builders. They were good self-promoters. When you realize the complexity of a building project or process, all the people involved – the people in the design team and the construction team, the people who supply and manufacture the products and all the variety of users – architects are only a part of the process. Granted, they are an important and influential part that can set the direction for the other players to do their roles. It’s the notion that some of these firms had – “It’s all about me, Mr. Architect” – that I had a hard time with.

When Abe, Mike, David and I sat down to talk about forming our firm, we asked, “What is it that we didn’t like about all the places we worked before, and let’s not do it again.” And so, it’s not a firm about us. It’s a firm about hiring and mentoring and nurturing people so we can become superfluous or leave and what we’ve created continues to do good things, acknowledging it’s a collaborative process where the architect has an important role at a particular time in that process. Master Builder? No.

What about the influence of technology on the industry?

Technology has an interesting influence on the profession, and it’s been important. Personally, I’m not savvy on a lot of it. I can draft well, and I can draw well, I can use ink, and I can use Mylar and all those kinds of things. If you were to think of a pencil on a piece of paper and then go to linen and then to Mylar, those are technological advances that improved the way you were able to do it. When we first put the firm together, we were using pin bar drafting and overlay drawings similar to what CAD became on the computer. It was the same idea of layering and thinking about how we improve what we do.

Technology was another tool that improved how we do things. The idea of building modeling, where you can look at ductwork conflict with structural conflicts, is very useful. Can I do it? No. Do I understand its value? Yes.

Advice to young people starting out in the profession?

I would say you need your education for what you learn there, but you really need to be open to real-world experiences. That is what’s going to determine your success.

I use the term “swagger” for the students who are good students, who come out of school, and they know everything, and they pass the exams right away and they’re doing great. That’s useful. But then there comes a point where they need to lose the swagger and lose the “I” strain and learn the word “we,” and understand the importance of the contributions of all those other players in the building process. We need to figure out how to work with all kinds of people. We don’t always get to work with our friends. Sometimes we have to work with people we dislike, don’t trust, and are uninformed or just plain stupid. The value is in figuring out how to make it work. Do you want to insist on being right, or do you want to be successful? This can be done without compromise of integrity.

Any other thoughts?

I went on the Heritage Foundation Board when I was a student; they recruited me because they needed somebody young. We were fighting the preservation battles: confrontation toe to toe at the intersections, screaming at each other over the Eagle Gate Apartments or whatever. And we thought, maybe we should get this in education and heighten the awareness of the historic value of these buildings at a younger age.

So, we started programs in the fourth grade, where they had Utah history in the curriculum, and in the seventh grade, mostly the fourth grade. I did that for 20 years. We covered thousands of students, tens of thousands of students, hundreds of teachers and workshops using architecture as a way of educating the students in community processes, the value of the built environment and how it influenced their lives. For school teachers and young people, it’s been a very good way as an architect to articulate what we do.

Who influenced you the most?

I had a history professor, Aziz Atiya. He influenced me on the value of education and disciplined learning. He was an amazing scholar and could lecture on some obscure crusade from 1100 for an hour and a half and you didn’t realize you were sitting in the class because he knew his stuff. He taught me that you have to know your stuff.

I learned a lot from Jim Christopher. I learned a lot of good things from Chris, and I also learned some things that I probably did differently. Abe Gillies was a master at understanding the technical aspects of construction and realizing the importance of your people. He had huge respect in the construction world because he valued what they did. That was an important thing for me to learn.

Last thoughts?

I’m glad I did it. It wasn’t what I thought I was going to do, but I think I did it well. And I had a good career and made a lot of good friends.

To watch the full interview, please scan this QR code:

youtu.be/c-vhqLu-_nk