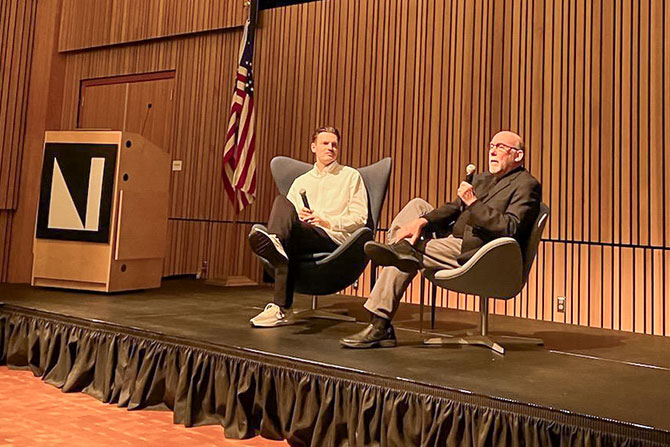

William Miller is a Professor Emeritus/Former Dean of Architecture and an Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Distinguished Professor. He talked to Fran Pruyn about his career, his time teaching, and his thoughts about architectural evolution in education.

When did you first decide that architecture was for you?

In grade school and high school. I grew up in Sacramento and, in 1948, we moved out to the East Side where all the postwar development was occurring. One day, a piano store moved in near my house. In the early 50s, pianos came in plywood boxes that were 4’x4’x8’. My friends and I asked, “Could we have those boxes?”

They said, “Yeah, we don’t need them.” We hauled them to my house and made a town with them and an old Army Signal Corps building from an Army depot. There was this little enclave of buildings we developed. Then in high school, I started taking art and mechanical drawing and really enjoyed that. We had some family friends who were architects and I talked to them about the profession.

When I graduated from high school, like most of my peers, I applied to three schools. We didn’t apply to Berkeley because none of us had the GPA to get in. We didn’t apply to USC because it was an expensive school. And we didn’t apply to Cal Poly Pomona because it was a huge school. I applied to Oregon, Utah, and Washington. I got accepted at all three, but I chose Oregon because a number of the architects I talked to who had gone to Oregon recommended it.

That was a really good choice. First, Oregon had a non-graded design system: you either received a pass or a no-pass. That was great because it encouraged risk taking and experimentation. You could go out on a limb with your design and fall flat on your nose and not fail necessarily. That was very positive.

The second thing was that Donlyn Lyndon, who was at Berkeley and was a principal at Moore Lyndon Turnbull Whitaker, became Department Head. Lyndon brought a whole range of new, young, very exciting, dynamic faculty, who were amazing. He belonged to a group, called something like “Architects Concerned for the Environment.” He had a symposium, and a group of people that came to the campus for a week. It included Michael Graves, Peter Eisenman, Stanford Anderson, and Henry Millon.

The first day there were design reviews, and a number of us were chosen to review our work. It was probably the most eviscerating review that I ever had. We had rough reviews at Oregon, but this was like, “Oh my God,” we were all stumbling around. Then every night they had lectures by the people who were there. The person would lecture and then there was a question-and-answer period. They were eviscerated too. “Oh, okay. I got it.” The issue is that architecture is about ideas and how you convey them. That week rendered the school inoperative for the next couple of weeks because we were all blown away. It was a mind-expanding activity. Because of that, I thought that I might be interested in teaching.

While I was in school, I worked for a one-person firm in Sacramento during the summers. I graduated in 1968 and went back to Sacramento and started work for a different firm, Dean Unger and Associates. I worked there for a while and then decided I wanted to go to graduate school.

Where did you go?

To the University of Illinois. I got a teaching assistantship. It essentially paid for my whole education there. Illinois was a much different environment from Oregon. Oregon was risk-taking, experimental. Illinois had a very strong tradition of producing and representing your work with a high level of craft. The discipline was a nice balance for me from Oregon.

When I decided I’d try teaching, I sent out about 70 letters and got some rejections. Then one day my wife, Beverly, called and said, “Oh, you have a telegram from the University of Arizona.” The Dean sent me a telegram saying, “Would you consider a teaching position at Arizona for this much a year? Please respond.” This was 1970. I hadn’t even interviewed. He just sent me the telegram and we went. When I got to the Arizona campus, most of my faculty colleagues had two schools in common, Oregon and Illinois, and the dean had been dean in Oregon. So, yeah, it was the old boys’ thing, before affirmative action.

Did you teach and practice simultaneously?

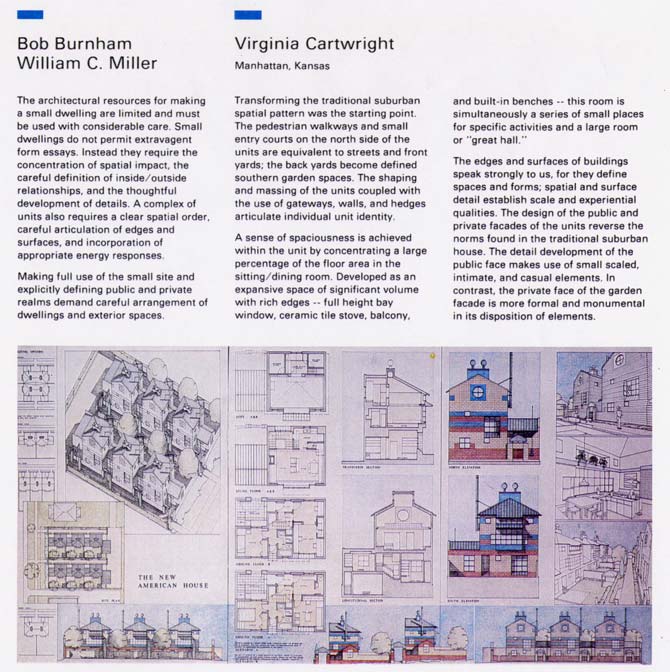

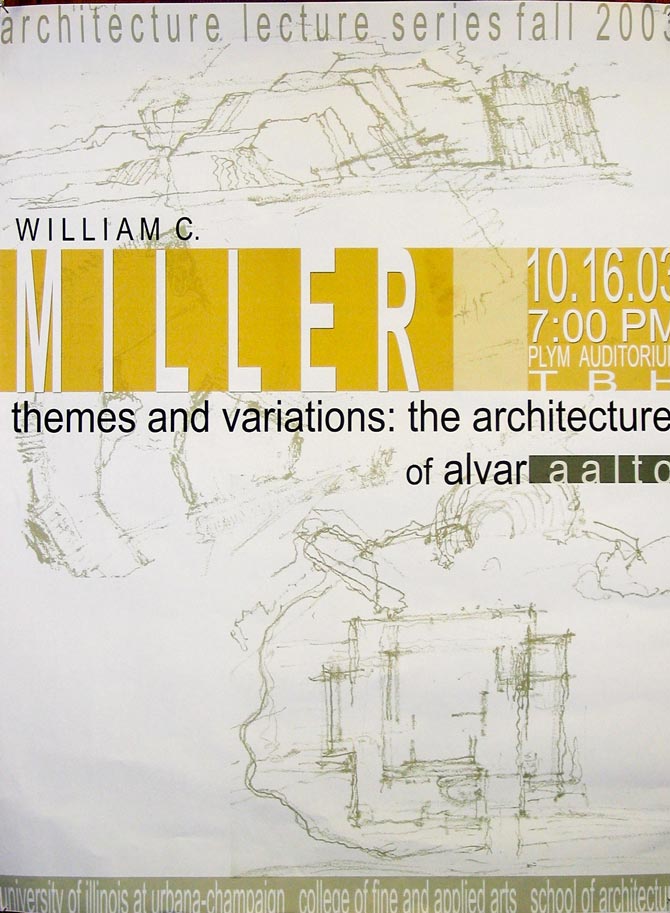

Most of the faculty had small practices, but at the first university breakfast I went to the university president said, “at Arizona, we publish and prosper”. I thought, “If I’m going to publish and not practice, what do I know that I could publish about?” When I was at Oregon they had a faculty lecture series. There were two lectures on Finnish architecture, and I saw Aalto’s work and thought, “Oh, that’s interesting.” During my fifth year I did an independent study on Aalto.

When I got to Arizona, I thought, “Well, I do know about that” and started developing articles on Aalto. My wife was also a teacher, so we went to Europe for the entire summer. We spent a third of the time in the Nordic countries, including several weeks in Finland. By that time, I had gotten more than enough visual material that I could say, “Okay, I’m writing articles, but I’m going to put out a letter to schools to see if they would want a lecture on Aalto.” Several schools responded, and I started lecturing. So, I had publishing and I had lecturing.

Then I decided I need to be registered. I always wanted to get registered even as an academic, because I figured it was only way that I could prove to the professional community that I had standing. Being a member of AIA also reinforces that to the professional community.

One of my colleagues had a friend who was a principal in a firm in San Francisco, a joint venture: Enteleki and The Design Company. Enteleki was a Salt Lake-based firm — Jack Smith, Frank Ferguson and Ray Kingston were all partners. They would come back and forth from Sun Valley and Salt Lake to San Francisco. I spent a year in San Francisco practicing full time. After that, I went back to Tucson for the next three years to teach studio and history theory courses.

What did you apply from your time practicing to your teaching?

I wanted to practice because you really need that experience to bring into the classroom. Students aren’t necessarily thinking about palpable things: How does a structure stand? How does it keep the rain off itself? And a whole range of very practical, straightforward things that buildings are all about. Teaching was setting up situations where you could impart that understanding to students and could begin to deal with those issues.

Also, there were three of us who were engaged in a research design project funded by the University of Arizona. They funded us to do schematic studies for an animal research facility. We looked at how to deal with animals, but also, more importantly, how to make it a sustainable complex. The study developed a design for the complex which included environmental, solar and air movement studies: concepts that focused on sustainability. It was never built, but it was one that the university touted to try to get funding for externally. That was more like practicing and teaching. We would get together in the mornings and work on that project, and then teach in the afternoons.

Talk about how you migrated to different institutions.

I’d been in Tucson for six years and was up for tenure and promotion. It was based on my research, publication, and lecturing. The first round it was denied saying, “Everybody else has been put up on practice. Why isn’t he?” The dean said, “We want to challenge this ruling.” Being somewhat savvy, I had already sent out feelers for other teaching positions. I figured the smartest thing to do is have something in your back pocket because you just didn’t know what was going to happen.

One of the places I had lectured was Kansas State, and I had a really good time there. They had an opening and I applied. They called me and asked, “You want to come and interview?” I did. When the dean said they were going to challenge my tenure decision, I told them it wasn’t needed because I’d accepted a position at K-State.

It was a good decision. Arizona didn’t really support architecture faculty the way they did at K-State. There, they said, “You’re going to go to Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture meetings. You’re going to present things, you need to get out of Manhattan, Kansas, a couple of times a year.” I was supported as an academic, as a scholar. For those 15 years I was publishing internationally and lecturing.

I became the faculty counselor for the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) and a regional director on their board of directors. I taught design and history theory courses, and I developed my Scandinavian architecture course. I gained a national profile, and became department head the last two years there.

Then we decided we needed to move back west. I was from California and Beverly’s family was from the Boise area, and our parents were not getting any younger. I was a department head and the only way I could move academically was as an administrator. One couldn’t move as a full professor. You just can’t do that in normal circumstances. There were three dean’s positions open: Utah, Idaho, and Washington.

I applied to all three and heard back from Utah. I came and interviewed. Then I got a call from Jeri McIntye, a senior vice president saying, “We’d like you to offer you the job. We want to negotiate.”

The next day, I got a call from Idaho saying, “Would you like to come and interview?” I said, “This is where I am with Utah; if we can reach an agreement, I will I go there.” The University of Utah has a great deal of advantages: You’re in the capital city; it’s the flagship institution; there’s only one architecture program in the state; and 85% of the alumni population is within a 90-mile radius.

I went home that night and said, “By the way, I got a call from Idaho this morning and they want me to come and interview.” My oldest son said, “Dad, Moscow, Idaho, is smaller than Manhattan, Kansas.” And Beverly said, “Go to Idaho if you want, but we’re not going.”

When you came to Utah, what did you want to do?

We didn’t have a consistent teaching responsibility throughout the faculty. Everyone negotiated with the dean. Some faculty taught one course a quarter while others taught two or three courses a quarter. The younger faculty were getting heavier assignments while some of the senior faculty were teaching one course a quarter.

One of the first things I did was realign the teaching assignments, putting out an analysis showing everyone’s teaching responsibility. The inequities were visually obvious. Then I put out my recommendation for what our teaching schedule should be. It worked well because it addressed another issue: credit hour production. With more courses being taught, more credit hours are produced. Our numbers went up, and resources from the university increased. We had one of the higher growth rates percentage wise in the university because we expanded our teaching responsibilities. Also, we admitted more students and we grew from about 36 students in the senior studio to 50 or 60. It was noticed by the university, and we began getting things that the school hadn’t gotten before.

Talk about the evolution in architectural education.

Architectural education, when I was in school and when I was first teaching, was a reactive process. You were given a project — a library here or a community center there or housing wherever. Students would propose a solution, you would critique it, and they would refine it. It was on ongoing cycle: Refine and critique. There were not articulated goals or expectations.

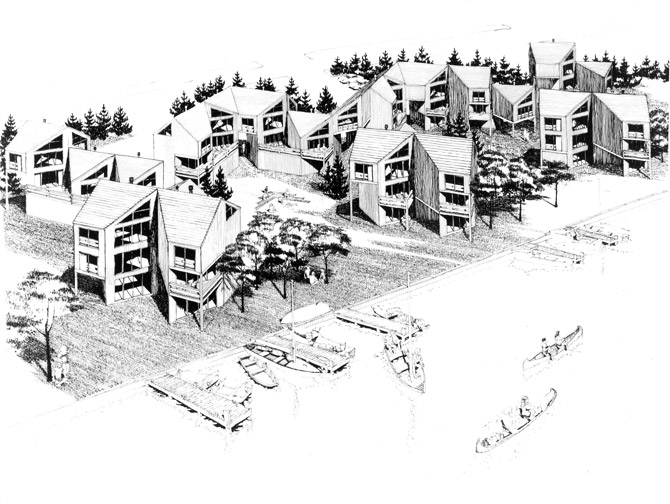

As time evolved, we front-end loaded design studio projects. You would start setting up clear goals and intentions, outline research exploration processes so the students could get involved with not only the building type, but (depending on what you emphasized in that project) it also could also be materially based. If the project was a summer camp, it was also a wood construction type, and explored ways to organize building complexes. The students would then focus on a building type AND an organizational type AND a material type. You evaluated them on their capacity to explore explicit ideas and issues.

Then, of course, there was the computer. That really impacted what students were able to do, what they’re able to explore, how they could explore it. As administrators, we had to ensure we had the resources we needed to be able to support the technology. That was one of the big things that I really appreciated at the University of Utah. We asked for hundreds of thousands of dollars to network the building so that all our students had computer access. That changed everything because the students could work at their desks, plug in to the computer, the Internet and the world.

Looking back, what are your most memorable accomplishments?

Besides doing it for 40 years?

As an undergraduate, I got interested in Aalto’s architecture. It became the scholarly journey I took throughout my academic career. It expanded to Finland and to the Nordic countries in general. It resulted in numerous articles, lectures, and presentations.

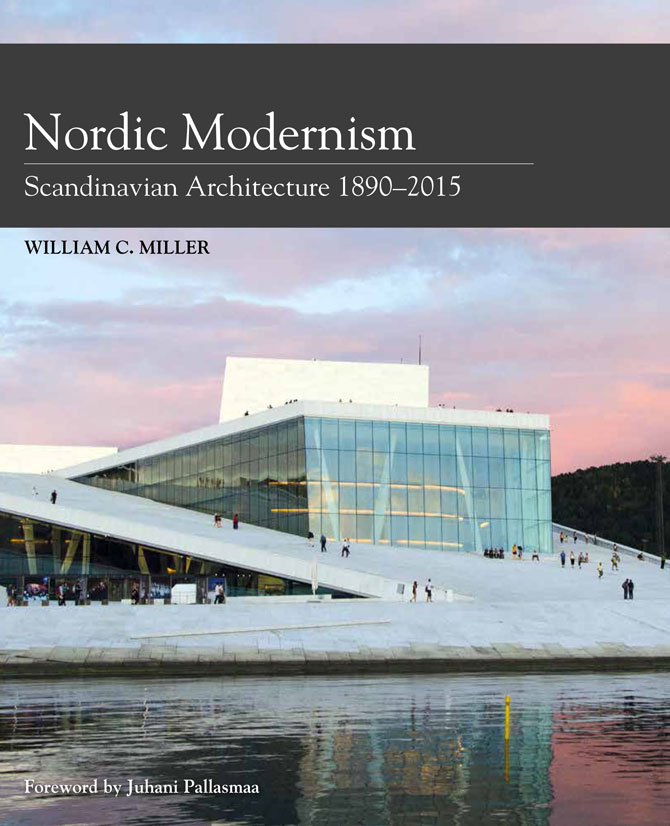

When I retired, my wife had Alzheimer’s and I became a caregiver. We traveled internationally for a few years. We went to China in 2014, for three weeks. Just before we left, I got an email from a publisher in the U.K. They said, “We’ve seen your coursework on Scandinavian architecture. Would you be interested in doing a book on Nordic modernism?” I talked to Beverly, and I emailed back, “I’d be glad to.” When I got back, I started doing that book. In 2016, my book on Nordic Modernism came out; it was the culmination of all my research.

And as Dean?

I was the Chair of a department that was probably over twice the size of the School at that time. The school was probably at the smallest it had been in years. Jeri McIntyre said, “The school’s profile needs to be enhanced. It needs to be blown up and things need to be happening.” I said, “I’m a Dean. If what this place needs is to up its profile, I can do it.” One way was through service. I had been on the ACSA’s Board of Directors. Once here, I was on the National Architectural Accrediting Board of Directors; I did two or three dozen accreditation visits over a four- to five-year period. I chaired NCARB’s Education Committee for two or three years. I chaired AIA’s Educators Practitioners Network. That service work was really important because it very much upped the profile of the school.

I also supported my faculty and all the things that they needed to do. In fact, I had to tell one faculty member, “Come in and ask me for money. Don’t go off on a conference without telling me because I’m going to pay your way.” Those are the kind of things that as an administrator I felt were really important.

I’m also happy that when I stepped down as Dean, the college had the highest percentage of alumni giving in the University. We established our first development campaign. That changed the profile of the school at the University level. As a result, they didn’t hesitate when we asked to network the building or for funds for salary increases.

Were there disappointments?

Oh, there probably were, but I’m not sure they were anything really big in hindsight. They may have been at the moment. Part of it was what I learned at Oregon — risk taking. It was a risk to go to graduate school. It was a risk to start teaching. It was a risk to change locations. It was a risk to become a department head. It was a risk to become a dean. Those kinds of things. There were things that would come along every now and then, but I don’t look back at anything that I consider really bad or detrimental. I feel very, very fortunate to have what I consider a fairly good 40-year career.

What would you tell newcomers to the field?

I think you have to be committed. You have to be engaged, you have to explore, you have to take risks. And you should not be afraid to do things like that. That applies to a lot of stuff, but I think it applies to architecture, simply because it is such a demanding profession and it’s such a demanding educational process. It’s much more complex than it was in 1963 when I started in architecture school.