Richard K.A. Kletting, an architect, has a name synonymous with several well-known buildings, including the Utah State Capitol. He was, in fact, the designer of well over 400 projects in Utah and the surrounding states. Born in Unterboihingen, Oberamt Nürtingen, Württemberg, Germany, in 1858, he was the son of a railroad contractor and the stepson of another. He trained early in life to cut stone. Kletting states in a memoir, “Most buildings in Württemberg at that time were built of stone. I was told that it would be a nice thing for me to learn how to cut soft and hard stone. Following this advice, I spent my vacation between school terms in a stone yard and gained a good knowledge of how to cut the different stones.”1

Kletting’s interest in design came early in his childhood. When questioned about his early years, he often told the story that his boyhood toys included mechanics’ tools and drafting instruments. Although Kletting’s family moved frequently, his parents always made it possible for him to receive private instruction from experienced teachers. Through those instructors, he was educated and trained in the classics, engineering and architecture.

His studies included geometry, physics, mechanics, drafting and various fundamentals of architecture. Notebooks that Kletting kept are filled with drawings of floor plans, elevations, molding details and brick patterns accompanied by copious notes. By 1874, when he was just 16 years old, Kletting obtained a position as a junior draftsman with the ever-expanding German railroad. During the year he worked in this capacity, it served as an apprenticeship and improved his drafting skills.

Following several more years of study, 20-year-old Kletting was awarded two professional projects. The state of Württemberg was finishing a railroad between Stuttgart and Freudenstadt, and Kletting was working as a draftsman in the Freudenstadt engineer’s office. The first project he obtained was designing part of a new city plan and a two-mile-long roadway from the railway depot to the town of Freudenstadt.

Kletting’s second project saw him in Lauterach, Bregenz, Austria, where he spent a short time working on a Roman Catholic Parish Church. Of the work, he says in his memoir, “I also spent a few months at Bregenz (Austria) on a church project for the city of Laut(e)rach.”2 He was working under architects Josef Anton Albrich and Alois Hagen. In the spring of 1879, young Kletting made a move to Paris. His arrival there launched his architectural education and began his evolution into a career as a designer.

He was employed as a draftsman and stone mason on at least six of the City of Light’s most impressive Second Empire and Beaux Arts monuments. Those included Crédit Lyonnais, Le Bon Marché, Basilica Sacre Coeur, the Paris City Hall — now better known as the L’Hotel de Ville, the Comptoir National d’Escompte and the Printemps.

He also served his one year of military service, which was mandatory for all young men in Germany. During this service, Richard was instructed to draw competitive plans for military activities. His creative plans won him a first-place award.3

Early in 1883, Kletting followed his brother, Oscar, to the United States and they both traveled westward, settling in Utah in 1883. The day after he arrived in Salt Lake City, Richard was hired by architect John Haven Burton, and together they provided architectural designs for two of the territory’s largest projects — the Insane Asylum in Provo and the University of Deseret in the Capitol City. A gifted prodigy of boundless ambition, Kletting soon created his own firm, started a night school and reorganized the Territorial Library.

All these activities brought Kletting into contact with future clients. He began designing everything from commercial buildings to residential homes to ecclesiastical buildings.

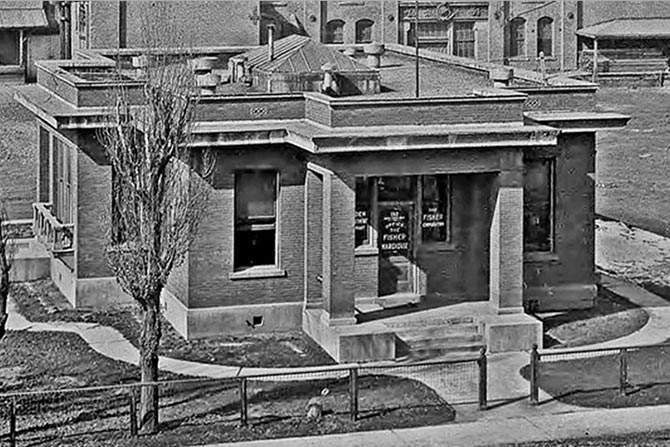

One of those clients was fellow German, Albert Fisher, a master brewer for the Salt Lake Brewing Company. Fisher was intent on creating his own brewing company, and with the backing of Aaron Keyser, he did just that. By 1884, Fisher had bought 15 acres of land bordering the Jordan River on 200 South in the western part of Salt Lake City.

Kletting began by designing structures for the brewery itself. He continued with additions and alterations as Albert expanded the operation. By 1912, Kletting created a six-room brick office. It housed a lobby, bookkeeping room, two offices, an employee’s lobby, a restroom and a vault. It featured large windows, Kletting’s signature skylight, maple flooring, and metal and oak fixtures. The Fisher office building was designed in the then-modern Prairie Style.

The brewery closed during state and national Prohibition but reopened after the repeal in 1934. The brewery’s glory days were between 1934 and 1955. In 1955, Fisher Brewery began a corporate relationship with Lucky Lager of California and, in 1957, was officially sold. Lucky Lager began to expand the brewery and by the fall of 1960, the Fisher name was removed. Lucky Lager became the General Brewing Company in 1963 and closed the Salt Lake City brewery in 1967.

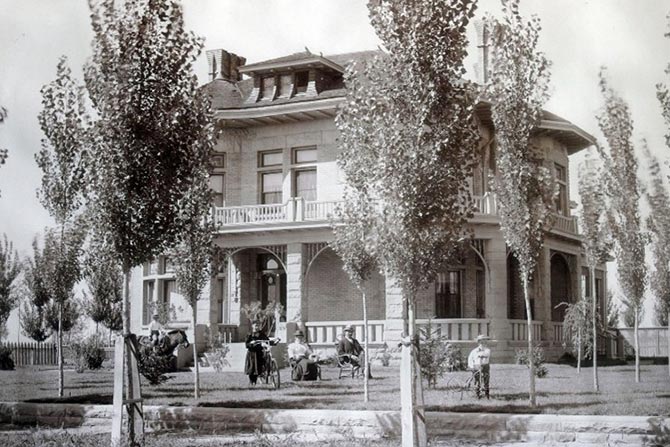

Fisher trusted Kletting’s design and construction prowess when, in 1893, he employed Kletting to design a mansion for his family on the brewery land.

Albert and Alma Fisher raised their children in this home. In 1901, Kletting designed a carriage house to accompany the mansion. It was later converted to accommodate cars. Although Albert Fisher died in 1917, Alma continued to manage her family and a vigorous real estate business from home. Several family members took over the brewery business, led by the oldest son, Frank.

Members of the Fisher family lived in this Victorian Eclectic mansion until the 1940s, when it was deeded to the Salt Lake Catholic Diocese and became a convent housing Our Lady Queen of Peace and Our Lady of Victory Missionary Sisters. By 1973, the Diocese used it to offer a home and counseling for independent living to homeless men with alcohol and drug abuse problems. As many as 40 men were fed and counseled, and up to 25 residents were housed in the attic dormitory (once the servants’ quarters).

The men’s labor included work-crew tasks in contract landscaping. On site, they kept the mansion’s masonry and woodwork in repair and landscaped the grounds. A 9:00 p.m. curfew was meticulously adhered to.

In 2006, Salt Lake City purchased the Fisher Mansion from the Catholic Diocese.

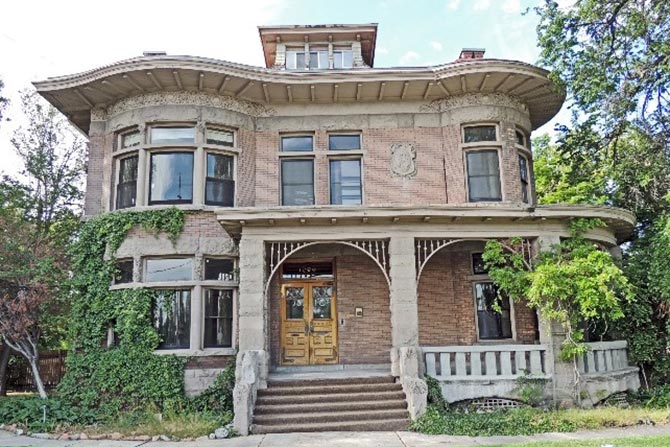

Remarkably constructed during the national financial panic of 1893, the Fisher Mansion is unlike any of Richard Kletting’s other large residences. During his over 40-year career, Kletting masterfully designed nearly 450 projects, including 50 types of buildings in 30 different architectural styles. Given its key elements, the eclectic Fisher Mansion leans towards Victorian Italianate or Second Renaissance Revival in style. This is due to its hip roof with deep eaves, its rounded, wrap-around porch, curved bay windows and classical detailing, including its bracketed cornice, foliated fascia, carved stone capitals and descriptive cartouches — a signature Kletting feature. Its original exterior doors, transomed windows, ornamental wood and stone trim are intact, although the stone is deteriorated in places.

The Fisher Mansion’s interior is mostly intact in its major rooms. The hardwood floors, fancy casework, stairways, fireplaces and even some light fixtures remain on the main and second floors. The west living room has been altered and the home’s rear additions were not designed to be compatible with the exterior architecture. The partially finished, open attic space has the potential to host sizable events if a second stairway is provided. The basement is mostly used for storage and mechanical spaces. Including its semi-finished basement and attic, the dwelling is four levels tall. Given the mansion’s several uses and years of vacancy, it is fortunate that its character has been substantially retained.

Behind the mansion is the Fisher Carriage House, which was also built of stone and brick in a similar style but was not constructed until 1901. Like the mansion, it features a hip roof, bracketed eaves, ventilating dormers and a projecting front wing. Above its main floor rooms is a single, large, second-story space. This was originally a hay loft but is now available for adaptive functions. Following designs prepared by CRSA, the carriage house was recently renovated and put to new uses, including city offices.

CRSA prepared an extensive Historic Structures Report to guide the eventual restoration of the mansion in the hope that its owner, Salt Lake City, would find viable uses for the building. At the time of this writing, the City is using a $3 million bond to fund a seismic upgrade of the structure, which was slightly damaged during a recent earthquake. This project is being completed by GSBS and its engineers. A nonprofit advocacy and support organization, Friends of the Fisher Mansion, has recently completed a master plan, prepared by Bim Oliver, to guide the remaining processes and advance the Fisher Mansion restoration and reuse project.

- Encyclopedia of American Biography 1947.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.