Private Public Partnerships (P3s) can be very useful forms of collaboration between government and private entities. They can also be disappointing. P3s can be a risky business, but the payoff might be well worth the investment.

The Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development considered P3 partnerships in its 2021 article: “Review of key challenges in public-private partnership implementation” and recognized that P3s are an effective tool for development, but that there are significant challenges in implementation. The challenges include the different organization cultures of the partners, unreliable mechanisms for sharing risk and responsibility, inconsistency between resource inputs and quality, monitoring and evaluation of processes and lack of transparency.

As Salt Lake City has inked a Participation Agreement with the Smith Entertainment Group for a Sports/Entertainment/Convention and Culture District, (providing the state approves the agreement by Sept. 1, 2024, and Salt Lake County can negotiate a lease agreement with SEG by July 2025) elected officials are eager to make this one work. It has been a fast and furious race to protect the two professional sports teams’ residencies at the Delta Center, and spur future development in the two blocks adjacent to the arena.

The need to revitalize Salt Lake’s downtown core is not a new thing. As Tony Semerad said in his recent July 29 Salt Lake Tribune article detailing past revitalization plans, “Reliable as cicadas, grand plans for urban renewal in the heart of Salt Lake City seem to hatch every 10 years or so.”

That said, let’s look at some of Salt Lake’s past urban renewal efforts, their track record, then consider what is on the table with the new agreement that was spawned by SEG’s acquisition of the Utah Jazz and the new National Hockey League team.

Constant reinvestment in a downtown core is critical to prevent urban decay. Salt Lake City has peculiarities that make that revitalization both inviting and perplexing. (See articles in this REFLEXION on the Salt Lake Plan and the Second Century Plan.) Chief among these are the large block and plat size and the extremely wide streets in downtown SLC, which, while making a city stroll feel more like hiking, also provides more possibilities for expanded green space and multi-modal roads.

Subsequent to the 1962 Second City Plan, each decade has looked to draw more people (especially tourists) downtown with the addition of hospitality, retail and entertainment venues and gathering spaces. Sometimes the efforts are entirely funded with taxpayer dollars (such as various iterations of the Salt Palace Convention Center, the Bicentennial Arts Project and Gallivan Square). On occasion, however, public entities have speculated with private developers to create a more vibrant downtown using private resources that are more ready and robust than what is available in municipal coffers.

The search for affordable housing and the now ubiquitous automobile literally drove people into the suburbs during the 1950s and 1960s. Prior to that, the city’s abundance of government centers, business, retail, entertainment, education, apartment complexes and, of course, the headquarters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, kept people on the streets day and often at night. Then, as people wanted to shop and work closer to where they lived, downtown became less attractive. City leaders recognized this exodus could leave the capital city hollow and derelict and looked for new ways to attract people downtown.

The Second City Plan was a detailed plan devised by downtown leaders and Utah’s Chapter of the American Institute of Architecture to drive more people downtown (see “The Salt Lake City Second City Plan” on page 16). The report suggested building a convention-cultural center (including a 2,500 seat music hall), a performing arts theatre, a visitor center, a transportation center for public transportation, a merchandise mart, a farmers’ market, hotels and motels, and parking. At that point, the LDS Church complex was under construction.

Since then, many of those recommended improvements have been built and rebuilt. There have been several major large-scale developments to transform parts of the City’s center. From the late 60s to the 80s, they included:

- Salt Palace Convention Center: First built in the late 1960s, and remodeled and expanded when the Delta Center was built in the 1990s. The Convention Center has had several additions and adjustments.

- Bicentennial Art Center: Included Abravanel Hall, UMOCA and a refurbishment of the Capitol Theatre funded by Salt Lake County and the Utah State Legislature and completed in 1978.

- Crossroad Plaza and ZCMI Center Malls: Built in the 1980s to attract suburban shoppers back downtown.

- Triad Center: Adnan Kashoggi’s 1980s three-phase grand scheme called for 43-story skyscrapers and 25-story residential towers.

Clearly, some of these projects have been more successful long‑term than others. The Salt Lake Convention Center thrived, but at the expense of an historic district with businesses operated by people of color. The Salt Palace construction took down most of Japantown, a vigorous center of Asian-run businesses by eminent domain, declaring the area blighted. The Triad Center went bankrupt after two phases.

In 1988, AIA Utah worked with the national AIA to bring in a Regional/Urban Design and Assistance Team (R/UDAT). A group of nationally recognized architects and urban designers teamed with local design professionals, city leaders and businesspeople to analyze the condition and the potential of Salt Lake’s Downtown. In its Executive Summary, the authors wrote that the city had “lost the critical mass necessary to a vital downtown.” The report included many recommendations including building a 20,000-seat arena, a 750-seat theater, historic preservation controls, a parking management plan, light rail, judicial/government center and large public plaza. A Retail District, a Convention, Cultural & Sports District, and an Arts and Entertainment District were called out. Several of these projects were realized through public finding, and other projects were initiated by private interests:

- Delta Center: Built in 1991 by Larry H. Miller Companies to accommodate the Utah Jazz and Salt Lake Golden Eagles. The land belongs to Salt Lake City.

- Gallivan Center: 3.65-acre urban plaza, including amphitheater and ice-skating rink opened in the 1990s.

- The Gateway: Just prior to the 2002 Olympics, the Gateway Shopping Center was built with taxpayer assistance by the Boyer Company. The open-air mall nudged people to come further west around the Union Pacific and Rio Grande Railroad Depots.

- City Creek Center: In 2012, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ development arm replaced the Crossroads and ZCMI malls with an inward facing high end retail center.

- Utah Theatre and its property on Main Street: In 2021, Hines Development negotiated an agreement with the SLC RDA to purchase, for free, the Utah Theatre and its property on Main Street, demolish the theatre and build a 31-story residential mixed-use project, that is to include a parking garage with publicly accessible rooftop greenspace. The residential tower is contracted to provide approximately 10% affordable units. At this writing, this project appears to have stalled, and Hines has applied to build a temporary parking lot on the Main Street sites until economic conditions allow the project to move forward.

Again, some projects were very successful — like the Delta Center and the Gallivan Center. But, after the opening of The Gateway, Crossroads and ZCMI Center languished. After City Creek was built The Gateway experienced an all-time high vacancy rate requiring it to become more office and entertainment focused.

Additionally, some facilities are built with an eye to more sustainable design and with higher end materials than others, which in turn makes the lower end buildings require upgrades sooner as the buildings need more extensive maintenance. (As a side note, buildings designed and constructed with taxpayer dollars are often built to a higher standard than private industry construction.) More recently, developers have built more and more multi-unit housing downtown. This is particularly noticeable as the post-COVID office building vacancy rates have soared, with many workers choosing to work remotely at least some of the time.

And how does that apply to the SEG development that is now on the table and, what do we know for sure about SEG’s proposed Sports-Entertainment-Culture District?

- The Salt Lake City endorsed a Participation Agreement with SEG on July 9.

- That agreement has been sent to the Revitalization Zone Committee for approval, which must meet a Sept. 1 deadline. Approval is anticipated, however if it is not, it will be returned to the SLC Council for further review and negotiation.

- By Dec. 31, the Salt Lake City Council must vote on a half a percentage point sales tax hike that will feed $900 million into the district over a 30-year period. They are likely prepared to proceed prior to that date.

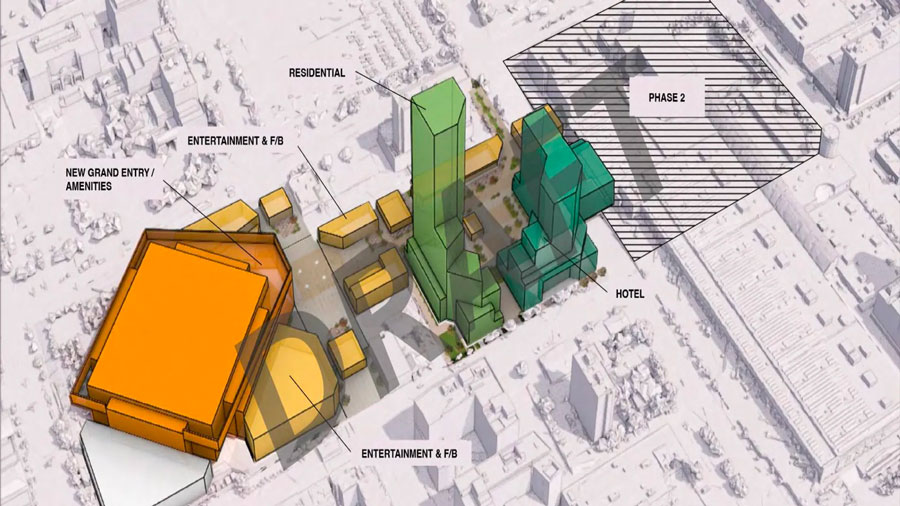

- The project area includes the block the Delta Center sits on and the two blocks east of the Delta Center. Salt Lake City owns the land under the Delta Center, the County owns the Salt Palace, Abravanel Hall and UMOCA buildings and their sites.

- Salt Lake planning commissioners voted unanimously to not recommend a zoning amendment to change building height restrictions from 125 feet to 600 feet, saying the changes don’t align with the City’s Downtown Plan. The city council reviewed changes to the D-4 Zoning District at its Aug. 13 meeting and voted on the changes at the end of the month.

- Salt Lake County must negotiate a lease of its properties to the SEG Group by July 2025, or the Participation Agreement is void.

Other terms of the participation agreement between SLC Corporation and Smith Entertainment Group include:

- The Jazz and the new hockey team must play all their home games at the Delta Center for the life of the agreement.

- A tiered ticket fee will be imposed on all tickets sold at the Delta Center. The proceeds will be put in a special city-managed Public Benefit Account. The funds maybe be used for any purpose benefiting the public, including affordable and family housing, the Japantown streetscape, improvements and recognition, and public art. One source estimates the amount generated in the Public Benefit Account, over time will be $10 to $20 million.

- SEG will sponsor apprenticeship programs, college internship programs, high school shadowing and youth program. Free and subsidized tickets will be offered to Salt Lake City-based community organizations.

What is still murky:

- Of the approximate $1.2B of tax money raised over 30 years, $900M will go to SEG — approximately $525M for the arena remodel and approximately $375M for district improvements. District improvements have yet to be defined. Although not yet announced, the remaining $300M has been rumored to be conditionally earmarked for potential improvements for the Salt Palace.

- Smith Entertainment Group (SEG) is still in the process of developing land use concepts and plans. SEG has issued renderings of Phase 1 that show a new Delta Center entrance, new plaza, pedestrian walkways, high rise residential and a hotel. The proposal calls for making 300 West between South Temple and 100 South a more pedestrian friendly environment by potentially undergrounding it. Phase 1 is scheduled for completion by 2028.

- The budget and timelines for Arena, Phase 1 and Community Benefit Account are stated in gross figures.

- The future of Phase 2 facilities, which includes Abravanel Hall, UMOCA and the Salt Palace is yet unknown. Improvements to these facilities must be administered by their owner, Salt Lake County. Phase 2 is scheduled for completion by 2033 (prior to the Olympics).

- Design guidelines have yet to be adopted.

- SEG has pledged to infuse $3 billion into the zone. That pledge is not binding and is not part of the Participation Agreement.

- The exact terms of how the project will be financed are still being discussed. Likely, Salt Lake City will issue a bond or series of bonds to make the money available up front and the sales tax revenue will be used to (re)pay those costs.

There is the opportunity to get this right and make a big difference, or to blow it spectacularly. Proponents say we must strike while the iron is hot, but critics claim that this project is moving too fast. Nonetheless, city, county and state leaders seem unified that this project will be transformational, even generational. The financial potential of this district is enormous; a 2022 consulting report stated a potential economic impact of $600 million annually from events at the Delta Center. Certainly, continual reinvestment in a community is the key to keeping it activated and attractive to local residents, tourists and businesses.

City Council Member Chris Wharton said in a recent email:

“In my view, this project — which represents the largest Downtown investment in Salt Lake City’s history — could only be possible through a public-private partnership between the city, county, state and SEG. Of course, it furthers SEG’s interests; they stand to make considerable profits if the project is successful. But it also keeps both professional teams (the largest single revenue generators) in Salt Lake City, it creates a new funding stream for the city’s immediate housing needs, improves access to amenities for residents and guests, allows us to help right a historic wrong inflicted on the Japanese-American community, adds greenspace and outdoor gathering space, encourages active transportation, boosts vitality in the Cultural Core, and generates the kind of significant economic activity and tax revenue that will help fund City services long after the 30-year agreement expires.”

We can hope this project, which looks like it will proceed, will be structured very carefully to have real, long-term benefits. All parties must be held accountable, terms must be enforceable, and the public must be part of the dialogue. To paraphrase Darin Mano, architect and city council member, “There is so much leeway for this to be incredible, for there to be mistakes made and for it be something we wish we had done differently.”

The local A/E/C community always stands to benefit from design and construction projects, and this is no different. No doubt much of the planning and design will be performed by out of state firms, but local coordination with local building authorities is essential and often collaborations between national and local firms provides opportunities for local firms to be significant partners in the process.

What makes a public-private partnership succeed in both the long and short term? There are no easy answers to that, but the Second Century Plan, R/UDAT report and P3 studies agree that it is best for the community to move forward together, rather than separately. One could also add that there is great benefit to involving the local design professionals in the conversation with the national designers, elected officials and business interests. No one knows the bones of our city better.

We hope that, in the interest of public participation, transparency and responsible use of taxpayers’ dollars, the urgency to implement this project is handled carefully to benefit those of us who will be contributing to its cost over the next 30 years. We don’t need to make those mistakes, Mano mentioned. The stakes are high. There was the Salt Palace and then there was Japantown. There are sports bars and then there is Abravanel Hall.