Architectural trade magazines all seemed to have found and featured Auburn’s Rural Studio at the same time, in the mid 1990s. My mind was littered all over the concrete floor, the expanding hand signal opened slowly up near my temple: my and other architects’ minds were shattered by the images of the Hay Bale and the Butterfly houses, a chapel made of tires, the community center fronted by automobile windshields. Really? Undergraduate architecture students? Designing and building all of these gems in what they call the Black Belt down around Newbern, Alabama, a rock skip from the border with Mississippi.

In addition to being blown, my mind was equally inspired, pondering the possibilities. Our firm, a couple of fellow former students and me, had placed second — the worst possible position, in a very real sense, emotionally and financially, first loser — for three or four impressively sized commissions in the past year. Deflated, we disbanded and lit out for positions in other, bigger organizations offering architecture. Except I never showed up to mine.

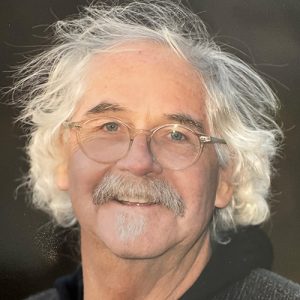

Instead, I invited Sam “Sambo” Mockbee, the Rural Studio’s founder, to come speak at a symposium I’d recently birthed with the School (we were younger than a college in those days) at the University of Utah, named for my grandmother Henrietta Johnson Louis, intended to awaken architecture students to the value of writing. And then, when selected for a prize, they spoke those written words in response to a guest, an artist tangential to our passion, someone like James Turrell, who we did entice, or Peter Greenaway, who might have been a stretch. Accurately by design, Sambo created all kinds of excitement. The dean, Bill Miller, and I had been talking. He noted the fair to say tsunami of interest.

Shortly afterward, the Utah Humanities Council, which I chaired at the time, sat in a small conference room at Liza’s Cow Canyon Trading Post, an annual retreat we made to the underserved corners of our state. The place wasn’t set up to be a space for conferences. As such, it was makeshift and layered with that dust that pervades the high desert around the Four Corners. It hazed; you could not easily discern faces across the tables set up in a U. The floor scraped with sand drug in by boots and settled in the veins of wide and worn wooden planks. You can’t avoid the stuff in Bluff; grit pervades, and it’s etched in the character of the hard people who populate the place, to the tune of 250-300, depending on the season, or probably more accurately, the year. Almost all of them are “creatives.” I looked farther, at the red sandstone beauty, the formations that lend the town its name, and it dawned. I was looking across the San Juan River, to the Navajo Reservation, a third-world existence not unlike Sambo’s Black Belt, not incidental to the learning, six hours from campus: students wouldn’t run home to nurse a cold.

I’d arrived at architecture fresh from having hand-hewn my own home in the Costa Rican jungle. We felled trees, Alaskan-milled them with chainsaws, hauled from the nearby riverbed and shovel-sifted gravel to size, and sand, found water in a falls about a kilometer up the canopy and piped it. It took three months to build the formwork and three harrowing and sweaty days to mix and wheelbarrow concrete. In total, it took a little longer than two years. It taught me a lot. An architect is behooved to actually, physically, shoulder together a living, breathing building. Talk about mind/body, think/make. Do, and understand.

A couple was selling their house in order to buy the agricultural rights, the final piece to save the farm central to Bluff. The stars were all seeming to align. I purchased said house built by a regionally famous rancher, Al Scorup, from quarrying sandstone cliffs in 1905. The rest, several years wrangling with General Counsels and Risk Management — three years proving mettle in and around Salt Lake City, bandstands, riverwalks, our own straw bale house for a family of Tibetan refuges — comprises the history: DesignBuildBLUFF, the program — the gift, the confidence — that keeps on. Twenty years. Bravo. Here’s to another 20 and more!