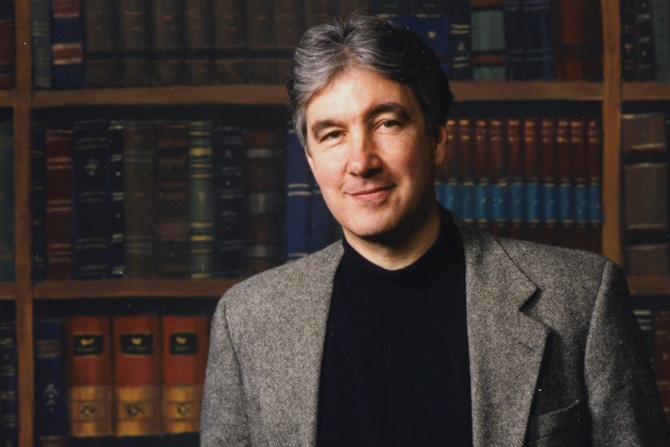

Cooper/Roberts Architects (now CRSA) was founded in 1976 as the only architectural firm in the region to specialize in architectural design for historic buildings. In this interview, Allen Roberts talks about his particular interests and specialties — history, architecture, painting, and writing, how his career unfolded, and how influential Wally Cooper was to it. Now, Allen has become recognized as a notable architect, architectural historian, author, gallery owner and fine artist. Not surprisingly, he had difficulty narrowing down his interests in the beginning.

When did you decide to become an architect?

Unlike Wally Cooper, my partner for forty-something years who in junior high school decided to be an architect,I started attending university without any idea of what I wanted to become. I just started taking classes (at Brigham Young University) in what I was interested in. I was just having a great time being a liberal arts student with no occupation in mind at all. I did that the first year, and the second year, and the third year, and finally, they sent me to a counselor, who said, “What’s your major?” I said, “I don’t have a major. I am just taking subjects I am interested in.” He said, “You can’t graduate in nothing; you have to pick something.”

It came time to register for the next semester, and they had come out with a new two-inch catalog of courses. I am standing in line there reading through it, and I see that they have a new Environmental Design Department and it had an architecture major. I thought: “Architecture.” I had always loved art and design, and before becoming a college student, I had worked summers with my father, a builder. I thought art and design and construction — that is architecture. “Why don’t I study architecture?”

After BYU, Allen went to the University of Utah for graduate education. He worked in Provo for a number of design firms, but his first employment after college was at the State Historical Society.

I have always loved fine art, history and writing. I always found it comfortable to do. When we had to do term papers, I would think, “Oh, great, I get to do research and write something.”

The job at the Historical Society was a natural. For three years, I was the state architectural historian, and that is when I met Wally. Both of us had some years working in architects’ offices. We met when he was assigned by his employer to work on the Capitol Theater remodel, and I was the historical architect administering the grant to restore the theatre. In conversation, we both decided to leave our current employment and start a new firm.

When was this?

May 1976. We rented a $30-a-month dusty space in the Guthrie Cycle Building. We had one client, which was a $300 gas station remodel. We basically had no clients. Other than the work we had done for others, we had no resume, no portfolio; we were 29 and 30 years old at the time.

Because of Allen’s national historic register experience and Wally’s experience with Burch Beall and Steven Baird’s architecture firms, they decided to specialize in historic preservation architecture. They would become the first firm in Utah to make that their core practice.

What were some of the struggles you experienced?

At the beginning, the biggest struggle for our small, emerging firm was we had no clients. The Historical Society gave me a one-year contract to continue doing the things that I had been doing for them all along as a consultant. Fortunately, 1976 was a bicentennial year, and the Bicentennial Commission had all these little preservation projects throughout Utah. We secured a number of those, so we were able to survive when we had very little income. We hired Anne Floor; she typed specs on a typewriter; we did all the drawings by hand. We had both started families by then and had three or four kids each, and we both lived in old houses that needed renovation, but it worked. We were able to survive that first year.

One of the first clients was the Wheeler Farm Restoration. We competed against the leading lights in the field. We were totally unknown, but somehow, we got that project. That included a historic structures report, then restoring the 1875 Dairy Farm of Henry Wheeler. A historic house and a missing barn needed to be reconstructed because they had been destroyed. All we had were footings and foundations and photos; there was an ice house and several other buildings that were moved or relocated or rebuilt, so it included all kinds of preservation projects.

Another early project that allowed us to do new construction was Ancestor Square in St. George. It was a 14-building complex on Main Street in St. George. The client had an existing building that he rented. We advised him to tear that down, keep seven of the historic buildings and let us do seven new buildings using indigenous materials from Pine Valley.

How did you structure your firm?

At the beginning, we worked together as a team, but within a few years, we both started developing our own teams specializing in different clientele and different kinds of work. I liked marketing and trying to secure new clients; Wally was really good at keeping existing clients happy, getting repeat work from those clients.

My personal interest was in the beautiful part, the design part, more than the technical part, but of course, you have to have some mastery over all those parts.

What changes have you seen in the architectural profession since 1973?

It’s become much more technical. When I took my architectural exams, there were 40 hours of exams, five days. The big design exam was held from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. For 12 hours, you designed a building. They gave you a little booklet that had the programming criteria, and by the end of the day you had to have a set of drawings. That was all done by hand, hand drafting.

Two thousand years ago, Vitruvius devised a formula that reduced the purpose of architecture to three words: utilitas — a building should be utilitarian and functional; firmitas — it should be built solidly; and venustas — it should be beautiful or attractive visually. I think that is still a good basic definition of what architecture is all about. My personal interest was in the beautiful part, the design part, more than the technical part, but of course, you have to have some mastery over all those parts.

Now all the drawings are done by computer. There are a lot more agencies weighing in on what is required for a building to be designed and constructed.

In addition to OSHA and safety requirements, we have LEED. We have buildings that are sustainable and non-toxic, and energy-efficient. We have buildings that are accessible. We do energy audits, envelope studies. There are a lot of technical overlays that really didn’t exist as much before.

When we started, there were no calculators. People were still using slide rules.

All of the new technology that has been developed has changed architecture so that it has become a very technical practice. I have to admit that I never got interested in CADD. I have never drawn a single line with a computer.

What do you think is the best building in Utah?

The Utah State Capitol Building has been rated one of the three most beautiful state capitol buildings in the country. And it is an exceptional building, really; the outside, the inside, the attention to detail, the use of materials, and now that it has been restored, even more so.

Another one that is a favorite of mine is the Manti Temple. That building is sited wonderfully; it sits on a hill overlooking the town, like a European cathedral looming over the small town below. It is a combination of styles: it has the buttresses, the mansard roofs on the towers, Second Empire, Gothic, Romanesque, a variety of styles that blended together into one eclectic hybrid. It’s a piece of architecture that works really well, and the architect used a local limestone: Oolite, which has platinized over time into this golden honey color that is quite beautiful.

What things are you most proud of during your career?

I was happy to have been able to help Wally build a firm from two people to whatever it is now. Literally, hundreds of people who have worked for the firm have designed projects all over the state, the country, even out of the country. I think we have done some really good architecture that will stand the test of time. I am happy about the firm, and I am happy about how my career went.

I am grateful to my forty-some-year partner, Wally Cooper. Wally and I both started without any understanding of where we might end up. I wonder what would have happened to both of us if we had not met; what would our careers have been like? I think this was one of those partnerships where we each brought something different but something compatible. We saw things the same way; we got along really well, worked together wonderfully and had we not met and created that partnership, the history of Utah architecture would have been different.

And projects?

I have been fortunate to have designed many different kinds of buildings, as well as written hundreds of reports and studies.

Twenty-Fifth Street in Ogden: I was in Ogden to work on another project when I noticed this street of commercial buildings from the 1890s to the early 20th century — derelict buildings, condemned buildings. There was a liquor depot. At one point, there had been 52 brothels; it was the “red-light district” for Utah. It was quite a place. I convinced Wally and my uncle to buy some buildings. We got one building for $4,500 and another for $12,000. I talked the City Council into creating a historic district and an LLC to fund a restoration of buildings. They moved the liquor depot and put in street plantings and site furniture; we did restorations. Now 25th Street is a great place to shop and dine.

There are so many, hundreds of projects. There are a lot of historic district nominations we helped create, like Capitol Hill in the Avenues, the Utah State Capital Historic Structures Report, the Farmer’s Union in Layton, Utah State House and Senate Buildings, Ogden High Remodel, the Thomas Monson Center. There were lots of projects in Park City, even a ghost town we bought in Chesterfield, Idaho.

What advice would you give to a young architect?

A lot of young students start out in architecture but never become an architect. I think they discover that coming into the profession as an entry-level, unlicensed drafter and designer, the compensation is less than other white-collar professions. So, you have to have a real commitment.

For me, and Wally too, it was never about the money. We practiced architecture because we had a passion for it; we loved what we were doing. That is what drove us forward, year after year, project after project, difficulty after difficulty. So, if you decide to do it, you should do it because you love it. When you think of a typical career — you start at age 20, and you go to 65, that is 45 years. You work 2,000 hours a year; that is 90,000 hours. If you are going to spend 90,000 hours or more doing your profession, you better love it.

Once you make that commitment, I think the rewards are there, not just the financial rewards, but the other kinds of things — the soul-satisfying, spirit elevating feelings you get from designing good buildings, satisfying clients, being a community builder, all of those things that architects espouse and practice feed the things that are most important.