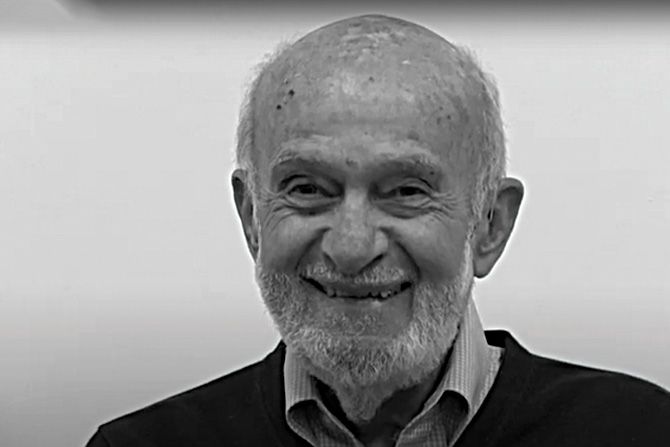

As part of our ongoing series of interviews with architectural legends, we are proud to present this interview with long-time architect Max Smith. He was gracious with his time, and it is with great pleasure we present this interview.

When did you decide to become an architect?

My mother died when I was young and let it be known she wanted me to be an engineer. Since I had very few opportunities to comply with her wishes, I started in engineering. The breakthrough day was inordinately hot; I was in an unairconditioned building, and there was a guy in front of the class with a giant slide rule attached to the ceiling who was telling us fledgling engineers how to use it.

I must have dozed off because I got a blackboard eraser right between the eyes. I woke up quickly. He kind of apologized but said it was very irritating to have someone just fall asleep in his class. If I had no more interest in the program than that, maybe this wasn’t the place I belonged. I sat there for a few seconds. I thought, “You know, the guy’s right.” I got up, grabbed my books, and walked out past him. I said, “Thank you very much. You’ve changed the course of my life.” I was aware of where the Architecture Building was. I’d been toying around looking into it. I walked into the building; it was magic. I thought: I’m home. It was funky and disorganized, and there was a hall where there were projects up on the walls. Then you went up a few stairs to the office. There was a lady there who was a legend. Her name was Johnnie Edwards, and she was the secretary and everything else.

I introduced myself and said I thought I might be interested in going into architecture, but I wanted to talk to somebody about it. She said, “Well, you can talk to Roger Bailey.” So, I’m sitting across the desk from Roger Bailey, who had to be one of the most magical human beings on the face of the earth. He’s just this handsome, gray-haired, rugged Abe Lincoln kind of guy. We talked, and I walked out on cloud nine, and that was really the inception.

Later, I found out what my mother meant by an engineer. It was an engineer on the railroad. So, I was on the wrong track to begin with.

I decided if I’m really serious about this architecture thing, (since I’d wasted time in engineering), I didn’t want to be bouncing around forever trying to get an education. So, I thought with my high school mechanical drawing skills, I might have some value in an office. I knocked on just about every door in town, and I got a cold shoulder in a lot of places.

I finally went to work for Stanley Evans, who had a little office on Fourth South over a coffee shop. I made my pitch to Stan. I said, “I just want this experience, and I’ll be happy to work for nothing until I become of value to you.” He looked at me like I was something that came in on his shoes and said, “If I pay you nothing, then you’re worth nothing. And I don’t need that.” Then he said, “Be here at 8:00 Monday morning.”

I started architecture school. I was in the old five-year program. I took rather naturally to it. When I graduated in ‘67, a mentor on the faculty, Stephen McDonnel, had me working in his little office at his home out in Millcreek. The University of Utah hired a brilliant man from MIT, David Evans, who started a program called Computer Graphics. It was a cutting-edge program, one of the first in the nation. It fed off the MIT program and was well funded by the Advanced Research Projects Agency of the Air Force — where the Internet was born.

David Evans saw the significant application of computer graphics and architecture. So Stan worked it out in the architecture department and became the faculty member who headed up the joint research program between Computer Graphics and Architecture.

I went to work for him for 18 months. For those 18 months, I was hungry to get out and practice architecture because that’s what I really wanted to do. But I became a research assistant, and we did some pretty interesting stuff. We wrote papers for ARPA and worked hand in glove with the computer graphics people. The computer programs applicable to architecture were born. The dream then was to take this to the point where a man building a project could flip down the front of his bib overalls and see exactly what he was assembling and then flip it back up and do it because the thing would exist totally in the computer. We were so far from that. It took 30 years to get where we thought we were going in that research project.

Next, I went to work for Edwards and Daniels, and I liked it a lot. I grew to know Ralph Edwards and kind of worked under the wing of Jud Daniels. There were a lot of interesting people in that office, and they were doing some really interesting work. I was there for close to three years.

My wife and I bought an old house on Wall Street, which was just south of the Capitol Building, and I started remodeling it. There was a thing called the Women’s Architectural League, and they put our little Wall Street house on a home tour. A lot of people were coming through it, and people responded favorably.

We structured the garden like a series of outdoor rooms, and that struck people because you didn’t see much of that in Salt Lake. All of a sudden, I started getting these opportunities to do gardens, and then I got involved in opening the house to the gardens, which lead to a small house remodel. There was a point where I got over my head in debt on the Wall Street house. I was working at Edwards and Daniels during the day, and at night, working on these little garden and remodel projects. One day it dawned on me I was billing a little more on my small projects by working weekends and nights than I was being paid at Edwards and Daniels. I was dealing with my debt on the Wall Street house rather handsomely, and I had more work than I could do. So, I resigned from E&D, and they were fabulous about it.

By now, we’d sold the Wall Street house and bought a house that was designed by Kletting, the architect of the Capitol. So here we were in this ancient Kletting house on Paxton Place, and I had the whole basement. I sat down there and drew my little remodel projects and started taking the licensing exam. It took a couple of tries.

A good friend from E&D days, John Huish, and I started a little, informal partnership, in a little building he had on Sixth Avenue and G Street. It was an old grocery store, and we started pumping out little houses. We moved into the bigger houses. We had a predominantly residential-based practice, and we’re doing a lot of work in Park City, which was becoming the ski place that it is today.

Then, John went one way, I went another, and I opened a small practice with a colleague from E&D. We bought an old building on South State Street, right across from the City and County Building, called the Jenkins Saddlery. There was a small hotel above and the old saddle shop on the bottom. We continued to do houses, and then some bigger projects started coming in that fed off our work in Park City, including the first Kimball Arts Center, which was a modification of a large old gas station whose roots went back to stagecoach times.

We moved from that building over to a wonderful old building off Exchange Place built during the First World War as a factory for fur-lined flight suits, although I think they never managed to build a flight suit there. I think the story was that they could never quite agree on anything.

We started doing some work in Jackson Hole. That grew into a small satellite office, and I spent a lot of time there. We did a major resort that was housing-based: 385 individual housing sites on the west side of the Snake River near Teton Village.

Through Steven Goldsmith, we were introduced to Artspace and became the architects for most of their buildings. They were a superb client. We spent a lot of time on affordable housing projects, and one of the last ones we did was the first affordable housing project that was net zero.

What work brought you the most satisfaction?

Clearly the affordable housing. I felt like I was doing something other than just fancy houses. We did a lot of fancy houses, over 400 of them. The firm still does wonderful houses for individual clients. Occasionally you found yourself in a situation where you had to finish a project that you didn’t believe in as much, but after all, it was the clients’ house. For the most part, we were able to do what we thought was good architecture. I had the good fortune of having colleagues who always put design as the primary mover in any project.

Lots of things grew out of the house projects. One client acquired a company in Salt Lake City and was interested in remodeling a house. Before we even got the house drawn, he had moved to another house, and we started working on that. Subsequently, his company leased the David Keith Mansion on South Temple, and in 1986 there was a disastrous fire that pretty well incinerated the interior of the building. The mansion has an open central atrium, and the fire was a catastrophe because the heat immediately blew out the glass; it was like a chimney. No one was hurt, thank God. The morning after the fire, I was standing in the still-smoking ruins, and my client said, “It can’t be saved, but we’re insured, so you might as well try and fix it.” That was a great vote of confidence. It turned out to be the inception of a whole new world of architecture for our firm. We never intended to be in historical restoration. But the building was insured by Lloyd’s of London for mega dollars, and so we commenced.

I look back on that, how little we knew, and how unqualified we were to even begin to think about a project of this nature. I knew a young man, Tim Hoagland, who was an incredible craftsman contractor. Tim was so bright, and I was so dumb. He said, “Max, I think there’s such a thing as an architectural conservator. I have a good friend who is a conservator at the Museum of Natural History. Let’s give her a call and see what’s the next step.” How do you know what to do, with all of the beveled leaded glass, all the wood, not to mention the Tiffany offshoot dome melted and in fragments on the floor we were walking on? So, we called Ann and she gave us the name of the historical entity that oversaw most of the historical monuments in the Northeast. The head guy spent 45 minutes on the phone with Tim and me. He said, “If you’re willing, I will send our key conservator out.” He sent a gentleman named Tom Gentle, who was there within two days. In the meantime, we had gone through the building using Tom’s instructions. We isolated all of the hardware putting a gel on them; we sprayed gels on all the glass to stop the acidic soot from etching it. We were doing all the right things. We loaded all the pieces of glass from the dome into boxes.

The dome was put back together by Willie Littig, a fabulous glass artist in Salt Lake, working under Tom’s direction. I could go on and on and on: the stories about the woods we found in Indiana at Stem Woods, a four-generation company; how we found flitches of flame mahogany veneers that were forged the same year the mansion was built. We succeeded. Lots of accolades. There was a wonderful party reintroducing Leucadia National to the mansion. We even got to take a bow; that was rewarding in ways other than dollars, but we were well paid, too. So maybe ten years later, the same damn thing happened to the Governor’s Mansion. Same thing right up through the middle. Mike Levitt was governor. And fortunately, Ian Cumming (Leucadia) went to bat for us with the state building board because we had no experience with them. The Salt Lake Tribune announced that “a nationally renowned architectural firm” has been put in place to restore it. I loved that. Nobody knew us outside Utah, although we did do some houses in Maine, and we did a house in the Puget Sound. But how do you like that? Nationally renowned! That led to the commission to do the Capitol with VCBO.

Then Artspace started buying these historic warehouses; the historical component married to creating new spaces called adaptive reuse. Then we started doing adaptive reuse for private developers, and they were a blast. The wonderful team of Tim Lewis and Mike Martin — just creative guys — developers who were out there trying to figure out how to do something that could be more interesting to the people who were going to live there. We did a number of projects with them: the Dakota Lofts, and the J.G. Macdonald Chocolate Factory, now known as Broadway Lofts.

What are the differences you see in practicing architecture in the late sixties, seventies and now?

I’m not sure there’s a lot of difference. At least there wasn’t for us. But maybe, maybe we didn’t change when we should have. A friend and I had numerous conversations, and he brought me up to speed on how whole systems are in packages in the computer, and how architecture in his mind had become a matter of combining these things into a building. I guess the truth is, I missed that whole part. I was starting to see it come in, when I left the firm in 2008.

Did you have any disappointments?

Oh, there were some terribly disappointing buildings, and there are a few of them out there. I’m not going to identify them for the record because they are embarrassing.

The unfortunate part of architecture is once you start riding that pony in one side of the stream, you got to ride it on through. We didn’t have anything ever fall and kill anybody. I’ll put that down to a bit of luck because we were out there stretching on occasion. One of the really positive things was dealing with the people I worked with. I think we were almost a family in a way. Sometimes there were people there who didn’t fit, so I can’t say everything was perfectly wonderful, but on balance, there are no regrets.

Any advice you’d give to younger people starting out?

Architecture is not something to love. It’s just a misuse of the word. But you can be, and should be, completely committed to it — but keep a balance. I lost sight of that balance a number of times. God love my wife; she went through those times with me, and we survived it. But it can really take a hold of you. I would advise anybody going into it today to keep a balanced life and develop some business acumen. I developed mine by making mistakes. There are ways to stretch your imagination and your muscles without taking inordinate risks.

Any final thoughts for me?

The profession can be a wonderful way to benefit humanity. And that’s what was so wonderful about Artspace. We always felt like we were really impacting the world in a positive way.

To watch the full interview, please click the link below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HK7FDZhECO0