As part of our ongoing series of interviews with architectural legends, we are proud to present this interview with Brenda Scheer, FAIA. It was a pleasure to interview her and to learn more about her fascinating career in developing urban planning and design programs in the state of Utah when there had previously been nothing. She truly is a role model for women architects. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you decide to become an architect?

After I’d already started college. I grew up in Oklahoma, and there were no architects anywhere near where I lived. I had no idea that was a viable profession for a woman. My dad always said, “You can be whatever you want to be,” which for a woman in the ‘50s and ‘60s was kind of unusual. So, I decided to be an engineer. I went to Rice University and was an engineer for about a semester.

I had a friend who was an architecture student, and she would carry around triangles and had drawings. And I thought, “That’s what I want.” They accepted me in the architecture school — they don’t usually let people in without portfolios, but I’d already passed muster as an engineering student.

Architecture school was very difficult. I was in a class of 25 people, and there were three women. I started school in 1971. It was especially difficult for women because they were harassed. We were harassed by fellow students; we were harassed by the faculty. Of the three women that started with me, I was the only one who finished.

What did that harassment look like?

One is outright harassment. You stand up in front of juries for a review, which is very tense and very difficult. The professor would make fun of my miniskirt, the way I was standing or what I wore. Another form of harassment was that they just didn’t give me any attention. I had professors who didn’t believe that women should be in architecture school. They wouldn’t come to your desk and give you a critique. When they did come over, they would just stare and turn away. The fact that I hadn’t worked construction in the summer or that I didn’t know how to draft were things that played against me all the time. I didn’t learn how to draft because they wouldn’t let me take a drafting class when I was in the eighth grade. I had to take homemaking. There were these obstacles at every turn. After a while, it became a challenge: “I’m going to show those guys. I am going to be what they think I cannot be.”

I graduated in 1977. I got my master’s degree. I had done an internship in Philadelphia with a firm that did urban design. I was very interested in urban design, and so I primarily worked in nonprofit planning organizations in Houston. I later worked in real estate development for a couple of years and then moved to Boston with my husband. He had a big job, and I was a housewife for two or three years because my daughter was a baby. I was not happy doing that. I really wanted to work. I wanted meaningful work outside of the home.

And again, people would tell me, “Okay, you haven’t worked in a while. Why would we give you a job? What do you know how to do? Can you do door schedules?” I hadn’t had any experience doing that sort of regular architecture. Eventually, I went to work for the city of Boston. It was a really interesting job, working in the neighborhoods of Boston doing neighborhood development. We would go into a small neighborhood, into their business district, work with people, give them loans and do design work for their facades. It was also my first opportunity to be the boss because they hired me to run this small department of six people. It was exciting for me.

We got some state grants. I had a great staff — mostly people from Harvard and MIT. It was great to be in the mix with wonderful people during a very volatile time when neighborhood development was a difficult subject in Boston. After a few years, I applied for a fellowship at Harvard, the Loeb Fellowship, which is a well-known honor that includes a year of study at Harvard. They select about eight or nine people a year. It changed my ability to see and understand myself.

It was great to be with the Loeb Fellows, many of whom went on to great things, and to have the experience of being at the Harvard Graduate School of Design with its incredible faculty. It made me understand architecture in a completely different light. I learned about architecture as a field of ideas, a field of philosophy and an expansive revelation about human life. It helped me become an academically minded person — to see architecture more broadly and as an important cultural touchstone.

And because it really changed my perspective, I decided, “Wow, it would be so great to be a professor. I think I have a lot of knowledge, things to give and a 15-year record of working in the field.” I went to the dean of the Harvard Graduate School, who had been a professor of mine back at Rice, and said, “I want to be a professor.”

He didn’t laugh or anything, he said, “Sure, I have these three jobs on my desk, which one do you want to do?” He just called up the people, and I got interviews. I knew nothing about academic interviews. They called me and said, “Want to come interview?” I said, “Sure, how about tomorrow? I’ll fly out tomorrow” (because this is the way business does business). Academics don’t do it that way. They have a three- or four-day interview where you have to talk to every single person on the faculty individually, and then you have to talk to the students as a group. You have to talk to the alumni as a group. You have to talk to the donors as a group. And you have to give a talk. When I landed at the airport, the professor who met me said, “We’re so looking forward to your talk.” I’m like, “What talk?”

This was not the time when you could go to your computer and pull up whatever you were doing. This was a time when you needed to have your slides all prepared. I had nothing. So, when I was talking to the graduate students, I told them my dilemma and they said, “Well, we have your portfolio here. Let us make some overhead projector slides.” And they did. I did the interview, and they offered me the job that day, which in academia, is unheard of.

I found out later it was really late in the season, and schools were desperate for people for the next year. I was the only woman again, and it was an advantage to be interviewing as an urban designer. So, I went to the University of Cincinnati. I was a professor of urban planning, which was a very good position to be in. Schools of Architecture can be hard on you, but my experience as a planning professor was great. Everyone helped me and mentored me. The students were terrific. I had great experiences.

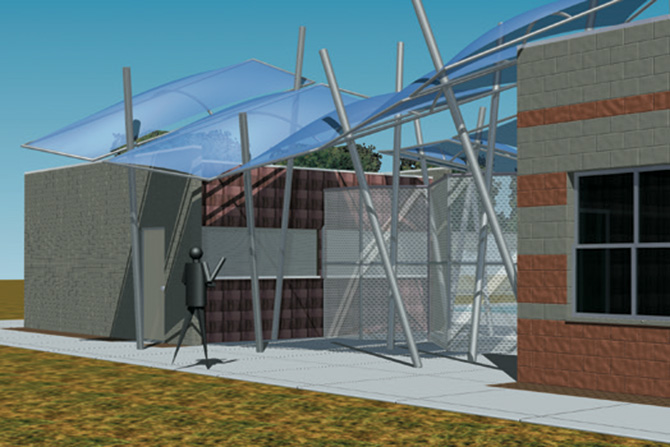

I began to write. I worked with people to write two books, and I wrote a lot of articles. I met my partner, and we established a practice in architecture. I was able to finally do a few buildings and work on many urban design projects around Ohio, Indiana and Kentucky. I became a more experienced professor.

After about 12 years, I was ready for a leadership position. I interviewed at the University of Utah for the dean position, which was unusual because I hadn’t been a department chair, but it felt really right to be there. My experience as an urban planner was one of the things that made me a good candidate for dean.

It was a small department: There were 12 faculty members and 180 students, and it was in a giant building. Faculty and students were spread out. As soon as I came, I wanted to build an urban planning program. It turned out there was an urban planning degree program in geography with one professor. With his blessing, we moved that program and renamed the Graduate School of Architecture to the College of Architecture and Planning, which was very pretentious because it really wasn’t that yet.

The urban planning program blossomed over the next five or six years and gained national recognition. The architecture faculty was really supportive. They taught some of the classes and sat on all the hiring committees. We hired some of the best urban planning professors in the country. It was a very collaborative experience for everybody.

The department had been very well run by Bill Miller, who had lots of great connections with local architects. But, beyond the architectural community, it was largely unseen in the general community. I encouraged the faculty to become more involved beyond the architectural community, such as the art community and the planning community. I sat on the board of five or six organizations like Envision Utah and Art Space and encouraged the faculty to do the same. They were on the Preservation Utah Board, the UTA Board, the Redevelopment Advisory Committee and so forth. We reached out and became much more widely known in the community. We also encouraged the students to get involved. We emphasized architecture as something that has a tremendous contribution to make in the community.

How long were you at the University of Utah?

Nineteen years. I was dean for 11 years. I continued on in the faculty for another eight years. The place had changed tremendously. We went from 12 to 25 faculty members. We had 184 students, and now I think they have 700 students. We added the Master of Urban Planning, a Bachelor of Urban Ecology, a historic preservation certificate and the Real Estate Development Program in partnership with the business school. The most important addition probably was the Multidisciplinary Design Program.

This is one of the great accomplishments in my life — introducing all of these interesting programs, trying to make them work together, turning the college into a real college with multiple departments and giving students in Utah the opportunity to do things that they had never had the opportunity to do.

Many of the urban planners that I work with today were products of the U’s Urban Planning Program. I am so proud of them because they have the chance to have those extremely meaningful jobs. Many go almost straight from their master’s degree into being the town planner. Utah had no resources like that before I became dean, and the faculty and I put that program together.

Likewise, for the design program, there was a tremendous demand for it. Now, it turns students away in droves. It’s something that captured everyone’s attention since the rise of the internet and social media. The design program was also developed to be a community resource. One of the first projects that we did was designing a prosthetic for people in places without access to high-tech prosthetics; so, we did low-tech prosthetic limbs. We had partnerships with the medical school, with the business school and with economics.

We had some really good leaders coming up, and so I stepped down as dean after 11 years and went back to the faculty. I did a lot more writing, got back to my research work and focused on my community volunteer work. I also did some travel and taught in South Korea in a program we had at the U.

Then you retired?

I’m retired now, but I’m not really retired. I’m still on the board of several organizations. I have been writing. I have published a number of papers. I organized a big international conference. I’m part of a research group internationally. I have been very involved in the Salt Lake City Planning Commission for seven years now and have been chair. I’ve been in the Utah Women’s Forum and continue to be involved in the Girl Scouts of Utah. I get a lot of personal travel in, and that’s exciting, too.

What are you most proud of?

I’m really most proud of my children. I have two beautiful daughters, and they are both accomplished in their own ways. I’m proud that they think of me as an accomplished mom. I think I set a tone for them that said, like my dad said to me, “You can be what you want to be.” That doesn’t mean that you have to be in charge of everything. It means that you can be what you want to be, which I think is a very important message to send to women.

I’m proud that I was able to be a role model for women architects in Utah. We started out not having a lot of architecture students who were women. Dean Miller had worked hard on that issue, but it still, I think, helped to have a role model in place there. I was a very visible architect in the city as somebody who was leading the school.

I’m also proud of what I accomplished at the university: the number of programs that were introduced and increasing the ability of students to study lots of new, different things. It’s important not only for the students, it’s also important for the state of Utah to have those resources available.

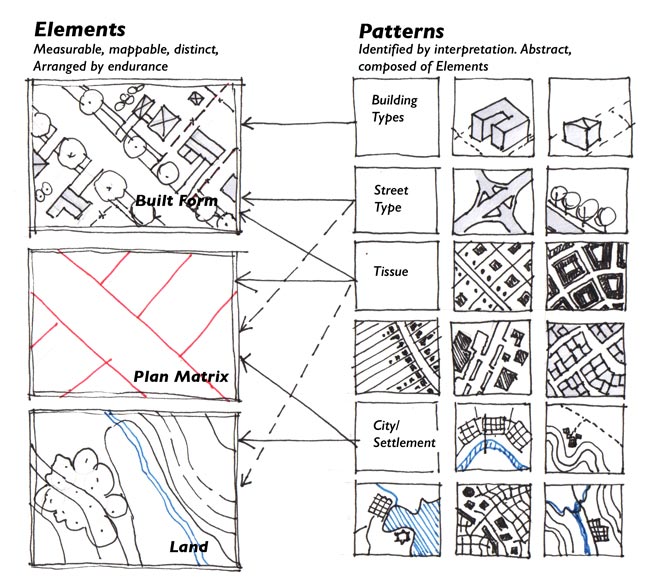

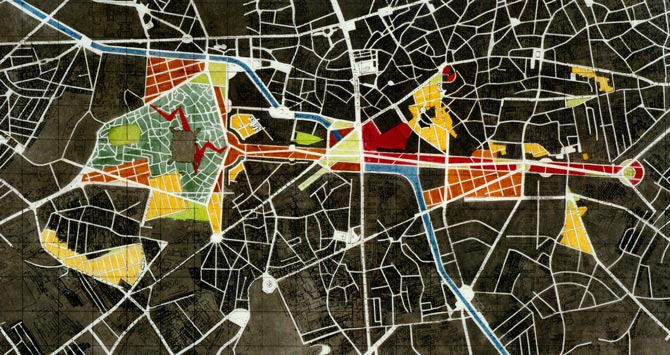

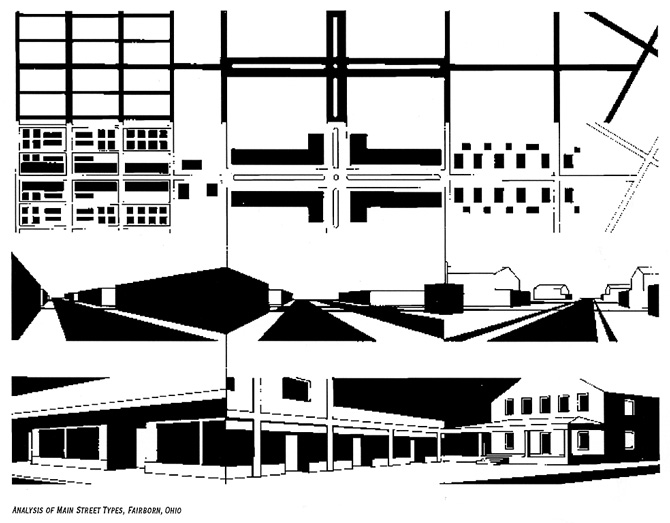

I’m proud of my research work. I have done a lot of research on urban morphology, which is the study of the history of cities. I’ve written 40 or 50 papers, I’ve done three books, and I have written a great article about Salt Lake City. Locally, people don’t know much about this part of my work, but internationally, that’s how I am known. A lot of my work is groundbreaking, theoretical and highly cited. That’s the academic measure that people use.

Any disappointments?

I would have liked to have been an architect in the sense of being able to design buildings. I did a little bit of it, but I did it in partnership with people who really did most of the work. I regret that I didn’t have that chance. I never thought I was very good at design until much later in my career when I actually found out that I was really good at design. Going back to my initial introduction to architecture school, where I was actually discouraged, I never realized that I could do that.

How has architecture evolved since you began practicing?

I think the evolution of practice has been really devoted to more and more computer-aided activities, which is kind of disappointing — not that it’s not great to have computers. It does cut out some of the grunt work. On the other hand, I’ve never noticed that it’s actually taken less time to do anything. Hopefully, it’s more accurate and more collaborative. Unfortunately, I think computer drawing has influenced architecture schools and the profession. Students don’t really know how to draw anymore or think with their hands as much because they’re going instantly from some little diagram right into the computer. The computer makes everything look beautiful, and everyone expects their drawing to be beautiful right from the very beginning.

I remember going to a conference not too long ago. A person was showing the urban design work of her students, and I said, “It’s very clear to me that your students know how to design an infographic, but do they know how to design a street?” The infographics were amazing; everything you could possibly want to know about that area was beautifully and graphically presented.

I think we lose something when everything has to be perfect immediately when you can’t just rip and tear up a model or sketch something a hundred times. Maybe we’ll be coming back to that more because the computer now allows you to sketch in it. I carry around an iPad and a pencil that I can sketch in, so even I don’t carry around a sketchbook anymore. It is the desire to be perfect right out of the bag that I think hurts the architect and the development of a design. So, I don’t think we see as much creativity as we could in architecture.

Advice for young architects?

I think the best advice I can give is to travel, to go to concerts, to get out of the architecture mindset and into the cultural mindset, so you are not just stuck doing architecture things in architecture courses. Go to the museum, look at art, talk about art and read all kinds of different things. So, I think the biggest advice I can give to architecture students is to aspire to be the Renaissance person.