As part of our ongoing series of interviews with architectural legends, we are proud to present this interview with David Brems, Principal at GSBS Architects. It was a pleasure to interview him, and we hope you enjoy getting to know him as much as we did.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why and when did you decide to be an architect?

Growing up in Lehi, there were not a lot of architects. My father, working hard to raise his family, had a side job building houses. I was the oldest of five. He took me out on job sites and handed me a stack of odds and ends of lumber to entertain myself. It was fun to look at the houses that were being built, how they were laid out and how they were different from the house that I lived in. It just got my imagination going.

I didn’t think a lot about it through high school, but I did well. In 1968, I got a scholarship to the University of Utah for tuition, fees and books. I entered electrical engineering because they had the beginnings of a computer program, but it was also an undergraduate degree to use to get into the Architectural Masters program. The Vietnam War was going on, so I decided my best option was to join the National Guard. After basic training, I came back and switched to psychology. I was anxious to get into architecture school, and that was the fastest way in. I started the graduate program in my last year as an undergraduate.

The first time I really recognized that this was a good place for me was while taking Tom Kass’s Basic Design class. Tom had studied at Cooper Union and Yale and worked as an assistant to Joseph Albers. He saw something in me and recognized that I was sometimes working three jobs to put myself through school. He said, “Why don’t you come and help me teach basic design as my assistant? Forget those other jobs and stay on campus.” That was really encouraging. I will always be in debt to Tom.

I also had the opportunity to learn from Bob and Anna Bliss. Bob was from MIT, and Anna was from Harvard. We had a number of faculty from Harvard. It was as good a graduate school in architecture, I think, as you could find in the United States at the time. I was also deeply inspired working with John Sugden. I can’t say enough great things about the school and how much I learned.

My class was small — 15 students. In 1973, the Arab Oil Embargo put the whole world into recession. When we graduated in 1975, it was a really tough time, and there were few opportunities. Somehow, I was lucky enough to get a job working for Ian Cumming at Terracor. It had a small architecture office called the Environmental Design Group, where I worked with another mentor, David Rohovit. I finished my internship, became a licensed architect and moved to Edwards and Daniels. It was an honor and a privilege working with Ralph Edwards and Jud Daniels. Jud was leading the design work and had just finished the (old) downtown Salt Lake City Library and Cottonwood High School.

After about seven years, I started my own firm. We won a number of Western Mountain Region and Utah AIA honor awards. Right next door to us was Ann Marie Boyden with et al advertising agency, and et al hosted the AIA office. I went through all of the offices of the Salt Lake Chapter and AIA Utah, working with Mike Stransky and Stephen Smith. Stephen and I were classmates and knew each other from school and had worked together at Edwards and Daniels.

We’d have breakfast once a week at the Hotel Utah and talk about what we were doing, the profession and what the future looked like. We decided to merge our two small firms — David Brems + Associates and Gillies Stransky — together. Abe Gillies ran the office and put out quality documents while Mike got us through any door marketing the firm. I love to design, work in the office and work on projects with our clients. It wasn’t very long after we merged that we added Steve Smith and became Gillies Stransky Brems Smith (GSBS). Many firms fail, but this one was a marriage made in heaven. It was very successful from the beginning. We prospered and grew every year from that time.

You are known for your work with environmentally responsible and sustainable architecture.

I went to college in the late 1960s and early 70s. There was a lot of change happening in the world and the beginnings of an architectural movement that I was quick to embrace. I believed that I owed a lot of people a lot of things and that I had a duty to help change the world. In my world, that meant changing architecture from being a resource-consumptive profession to one that was more environmentally responsible. We began designing passive solar homes and buildings that had natural ventilation and admitted lots of natural light, attempting to reduce the energy use of the buildings and make them more responsible.

Talk about some of those projects.

One of the very first projects was a double-envelope twin home I designed for a client in Emigration Canyon. When his partner fell out of the project, I bought into it and helped build the project. It was a lot of fun. It won an AIA Honor Award in Utah and a Western Mountain Region Honor Award.

We started designing a number of other houses in Utah; I think they all won AIA awards. We did a base ski facility and worked on a hotel at Brian Head, Utah. They were great clients who propelled us forward and helped us gain distinction as a design firm. The design awards were helpful in being appointed to the AIA National Committee on Design. Being involved on a national level and making friends and working with national-caliber design architects introduced me to people that I wouldn’t ordinarily know.

I chaired the 2002 Olympic Sustainable Facilities Committee. When GSBS pursued the Speedskating Oval for the Olympics, we brought in ARUP from their New York and London offices. They were doing a lot of sustainable work. The day we interviewed for that project, Kevin Miller and I walked in and said, “We’re going to design the world’s fastest sheet of ice.” It was an interview like every other interview, and everybody on the other side of the table was going, “I can’t wait to hear THIS story.”

By the time we’d finished, we talked about the environmental aspects of the project and how we would be able to control temperature, humidity and ice temperature. I think we enticed them. They thought there might be a chance to create the world’s fastest sheet of ice. Wouldn’t that be something to offer in the 2002 Olympics? We were awarded that project, and we did create the world’s fastest sheet of ice. The Oval was one of the first pilot LEED-certified buildings in the world, and 20+ years later, it’s still the world’s fastest sheet of ice.

Talk about the structural system; that was a huge part of doing it right.

Sometimes it’s recognizing other people’s great ideas. We initially designed a building that had the skin on the outside of the building. It enclosed a huge quantity of space. We were meeting one day and evaluating structural systems. This was a really great moment! One of the structural designs we were looking at was the cable system, where the structure was on the outside of the building. It was the most expensive structure; it was the most expressive structure.

We were thinking, “We’ll never get this; we will never achieve this.” Our mechanical engineer from ARUP was paying really close attention and doing calculations of the volume of the space. He said, “If we put the skin on the inside of the structure, we reduce the volume of this building by about 50%. The mechanical system gets smaller, the electrical system gets smaller and the amount of energy to run the building is a lot less. I think will even out.” When we value-engineered that idea, we ended up with a lower-cost building with a more expressive structure that was able to achieve the world’s fastest ice.

Share some of your favorite projects.

To date, GSBS has completed nearly 40 LEED-certified buildings. Another really great project is the Salt Lake Public Safety Building. We had plenty of sustainability credentials to pursue that building. We also had really good law enforcement and public safety credentials, and that came together for us. That building is a LEED Platinum building. It is a net zero building. The community loves it, as well as the police and fire who are its occupants.

Sometimes the stars align and everything comes together. I’m especially proud of putting together the team for the Museum of Natural History. Mike Stransky, through his involvement as an AIA Regional Director and national board member, was key. He knew many great architects in the country. He met Joe Fleisher, an architect from James Stewart Polshek’s office. We became great friends as firms. Joe did a peer review of our firm and made some important observations that helped us correct our course in a number of ways.

I toured the Rose Center for Earth and Space at the American Natural History Museum in South Central Park, which was Polshek designed. When the museum came along, I knew exactly who to call. We put together a great team and pursued and won that project. We’re still working on the museum. We’re working on a plan right now to electrify the museum, taking all the carbon-based fuels out of the museum and anticipating it will be net zero.

How has architecture evolved since your early days?

When I was in architecture school, everything we did was by hand. There was an inkling of computers. The beginnings of computerized graphics happened at the University of Utah. When I was in electrical engineering at the University of Utah, I ran into people like Evans and Sutherland.

I credit Abe Gillies for seeing early on that there were ways to automate processes. We were an early adopter of pin bar drafting (which was really the beginning of computerized drafting) even though we were still drawing with pencils and pens on mylar at the time. We would draw in layers: the footing and foundation is a layer, the floorplan is a layer and the ceiling plan is a layer. Then, we would put all those layers together and run sets of blueprints from those layers. It’s exactly what we do on a computer today; it’s just automated. All the layers are there; they’re just easy to manipulate. Then, we moved into Revit and three-dimensional design and created three-dimensional models of our buildings.

I’ve been a little reluctant with all of that. I worry that we get into the computer too soon and that don’t spend enough time thinking strategically about the problem that we’re trying to solve. In some ways, with computers, it becomes too late to make a lot of changes.

In ‘79 and ‘80, architecture was a men’s game. There was one woman in my architecture class who had to drop out for family reasons. Now, I think more than half of the architecture classes at the U are women, and there are certainly many minorities. GSBS has consciously tried to be more inclusive and offer opportunities to others. We’ve discovered that it makes us better architects, better human beings and more sensitive to others’ issues. We’re diverse, inclusive and multidisciplinary in many ways now. It is really fun to work with people with so many different backgrounds and educations in our firm.

Disappointments?

Sometimes, you invest emotionally, intellectually and financially in the pursuit of a project that you really want, and it doesn’t work out. There are great personal losses and loss of resources. There are disappointments to the people in the firm who we want to convince that we really do know what we’re doing.

My personal disappointment is the loss of some of the people I consider friends, mentors and staff. When you lose a key person in the office, for whatever reason, you always stop and say, “Isn’t there something we could have done to work this out?” I think losing important people is harder than losing projects.

What do you love about architecture?

I believe I owe the world something for the privilege that I’ve had. I think I’ve inspired a few people, at least within environmental design, to try to make the world a better place. The sad part of being heavily involved in it is realizing how much more work we have to do. The amount of change we have to create as architects is huge, and we’re still not all on the same page. I think the environmental architecture movement and creating LEED … those are all really good things. We have a profession that’s deeply capable of making the change that we need to make, but we have a political and social system that is standing in the way of our profession doing what we know how to do.

Advice for young architects?

Sometimes, I teach at the architecture school. It’s a great opportunity to meet students and see some of the talent. I think we’re getting architects who are really proficient at using computers to design. Computers allow us to look at really beautiful renderings quickly. But 100 views of a bad idea is still a bad idea. Sometimes, it’s easy to seduce people with really beautiful renderings. I look for people who are able to think critically and try to define the problem before we start looking at three-dimensional architectural solutions. We can talk strategically about how the project fits into the community and how it relates to the environment. We can bring those ideas together more deeply than by just creating some space, spinning it around and looking at it with a computer. I love computers, but I also am afraid of them being used too soon in the design process.

It’s amazing seeing how the new talent goes about doing what they do. You can see pretty quickly if a person is able to put themself inside of their idea. Are you inside of the space when we talk about the quality of the space, the dimensions of the space, how the light comes into the space and how you circulate through the space, or are you just seeing that on a piece of paper? There are very few people who are able to put themselves inside of the design and be a part of and wear it. Architects are people who can safely design a building, get up in it and make it function, but a really great piece of architecture inspires people. It says something about society. It says something about the time we live in. It says something about our hopes and aspirations for the future. It’s more than a building. It’s a very sophisticated work of art. It’s hard to come by, and it doesn’t happen every time.

Last thoughts?

When we started, Utah was a pretty utilitarian place. The first really great building in a long time was the Salt Lake City Library by Moshe Safdie. That building, I think, made us feel good about ourselves and helped us, as a city, realize that we deserve the best architecture. I think it raised the bar. Buildings like that — and the Speed Skating Oval and the Museum of Natural History — are easier to achieve today because we recognize what is good, and we always want to do something better. It’s been fun growing up in a place that has gone through so much change and so much growth. It’s a great place to be an architect.

Of course, the other side of architecture is the amount of knowledge and information that goes into every building to get it built and the incredible amount of risk that we take. It’s an incredible production to put up a large, complicated building and have a reasonably good chance that it won’t fall down in an earthquake or somebody is not going to fall off of it.

I’m very appreciative of all of the people who have helped me in my career, and I hope that I’ve helped a few others along the way. I’ll probably continue to do what I do until I die. I’m happy that my current partners see value and that I’m able to continue to work. It’s what I really like to do. I’m much happier coming into the office every day and taking on a new challenge. Architecture is a great profession because it really doesn’t have an end to it. You’re not a pilot who can’t land the plane anymore. Maybe we fade out, and our ideas aren’t valid. But I do think critical thinking skills will always be valuable. I’ve had a good career. I think my family is proud of me, and it’s created opportunities for them.

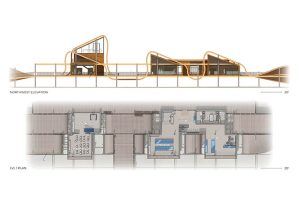

Utah Olympic Oval & Kearns Athlete Training and Event Center

Salt Lake City Public Safety Building

Weber Basin Water Conservatory District

Saint Thomas More Catholic Church

Jordan Valley Water Conservancy District

Utah Olympic Speed Skating Oval