Standing Tall

Tooza Design

“Standing Tall” is a modern interpretation of the famous lady justice sculpture, with her blindfold representing impartiality, scales to weigh evidence of the accused, and a sword to exercise an appropriate verdict. Tooza Design’s interpretation sets the Lady Justice atop a series of precast benches, that progressively change shape from random and angular, to uniform and regular. This represents the process of the District Attorney in bringing order to chaos.

15’ x 10’ x 18’

Precast Concrete and Corten Steel

Salt Lake County District Attorney Office, West Jordan, UT

Art has been integrated with architecture since the dawn of humankind: cave paintings and sculpture gardens, ornamental hardware and draperies, decorative cornices and sconces. And, of course, the stone, steel, glass, wood and concrete used to build structures create their own kind of art.

Utah, which has always valued visual, literary and performing arts, has a plethora of beautiful art installations peppered across the state that was funded by taxpayer dollars. How to choose them, how to incorporate them into buildings and how to make them last are concerns artists, architects and arts administrators in civic government address daily. I talked with several people who are deeply involved in this process and will share their thoughts — but first a little background.

“Art” itself has always been an abstract term. It is defined loosely to embrace many forms of expression and creativity, but until the 1930s, American public art was routinely limited to paintings, statuary and stained glass that were used to tell a historic narrative, to glorify founders, or to memorialize war heroes, veterans and prominent political figures. Certainly, buildings were often ornamented, but these embellishments were often considered decoration and not “fine art.”1

Publicly commissioned statuary, paintings, windows and sculpture tell the stories of the place, the time, the history and the culture in which they were created. However, one generation’s hero can be the next generation’s dastard. George Washington’s soldiers and citizens tore down a statue of George III, cut off its nose and melted the rest down to make bullets for the revolution. Today, we are seeing murals and statuary being removed, replaced, and defaced.2

That is why, now, when we choose public art for a public place, built with taxpayer dollars, it is critical to choose wisely. 1) The art must be more than embellishment or ornamentation but tell a story. 2) It must speak to the setting where it was created. 3) Since public art communicates the values, people and events that the community wants to be remembered (and sometimes commemorated), it should reflect the culture and period when it was created. 4) Finally, it should last, both figuratively and literally; it must pass the test of time. This last criterion is by far the most arbitrary, challenging and important.

Motivated by relieving the impact of the depression on artists and to encourage a national pride in American culture, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal enabled the standardization and regulation of public art by instituting the Art in Architecture’s program’s one half of one percent for art program. One half of one percent of the construction cost of government buildings was reserved for contemporary American Art. Major tenets of this program were that art was required to be accessible to the public, site specific, and celebrate the people of America. This too had challenges as the early programs had propaganda goals, but much of this structure is still in place across the United States.

The entire concept of public art changed drastically in the 1970s, when artistic efforts formed an alliance with urban renewal.

Milling Around

Tooza Design

“Milling Around” is a two-story wall installation made up of hundreds of athletic shoes. It has reference to the rec center’s purpose as well as the history of the area. The shoes are a nod to the function of the building (a basketball court and jogging track), and the shape refers to the grinding circular mill stones that were part of the site over a hundred years ago.

21’ diameter

Athletic Shoes

Millcreek Recreation Center, Salt Lake City, UT

Artists found opportunities to be interactive, relational and were chosen and curated by public selection committees. They embraced public movements like environmentalism and sustainability and designed pieces activating the setting in which they were placed. Public art became more about the public. As Nancy Boskoff, former Director of the Salt Lake Arts Council said, “Not always, but more often, public art has turned toward more reflections of the community and the location — appropriate because the works are in public spaces and paid for with public money.”

As time has progressed, artists who seek commissions in the public realm with taxpayer money have become sensitized to what the public contemporaneously believe is an appropriate use of its money. The process itself has become more public, and representative selection committees are often utilized to select artists and/or artwork. Although public art certainly can still be divisive, the public funding process has made it far less prone to political controversy. As abstract art has been added to more figurative and representational works in public collections, it is more likely that the public will ask, “But is this art?” before they topple it because it offends their political or social sensibilities.

Salt Lake City, Salt Lake County, and the State of Utah all have varying but similar public art programs. Valerie Price, the former Salt Lake County Public Art Program Manager, talked about the process the County uses to select artists and art for its architectural projects.

“It is completely up to the Salt Lake County Council to determine if one percent of the construction cost should be dedicated to public art. When that money is in place, the Design and Construction team will determine where the art wants to be. That will be decided by the usage of the building and how much public space is available. Should it be on the exterior or the interior? If it is interior space, then the public has to have access to the space.”

Once the RFQ is written, the scope of work, the background, and the nature of the art (sculpture, mural, painting, etc.) that is desired, then the public art selection committee is assembled. In Salt Lake County, that typically is comprised of seven to nine people, including the architect, the client, the contractor, people from the art committee, the artists and people from the community. Valerie added, “When you put together your selection committee, you have to be very wise who you bring in. You should not give too much power to one or two selectors. It should not become political.”

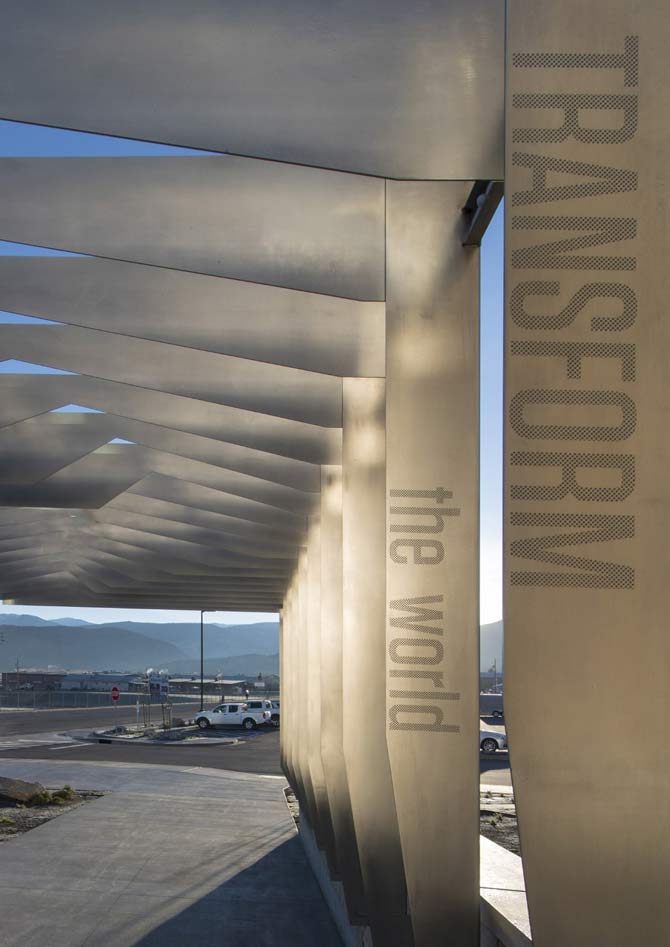

Transform the World

Tooza Design

The shape of each fin in this canopy sculpture progressively transforms into more dynamic forms as one walks under the canopy. The result is an organically flowing feel as one moves through the structure. This transformation is a metaphor for the students that attend the school — as they work hard, they can transform their potential and have the ability to impact the world in positive ways.

10’ x 12’ x 27’

Etched Stainless Steel

LED Lighting

Southwest Technical College Campus,

Cedar City, UT

There are typically two ways to choose the artist for the project. Committees will commission a piece of art based on a site-specific mock-up, or they will hire an artist based on their portfolio, reputation, and experience, and work with the team to create an appropriate piece of art. Like architecture selections, the proposals are evaluated and then short-listed, then, according to Valerie, “there is a real conversation, sometimes as part of an interview, about what the piece is going to say, what it will depict? What will best complement the architecture?”

Valerie enjoys working with an architect who is also an artist, as they understand both the practical and conceptual sides of the project. Rob Beishline, AIA, is just such a person. Rob started his undergraduate work at Weber State in 3D Design. He transferred to the University of Utah and majored in architecture, completing both undergraduate and Masters work in architecture. Rob works four days a week at Method Studio as an architect and the fifth day with Tooza Design — a business he and his wife founded to do art installations, many of which are projects funded by taxpayer dollars. They do three to four art installations a year.

Rob prefers doing a mockup of the art to win a commission, rather than submitting an application/portfolio, which is significantly less time intensive. “Although it can take many hours, sometimes hundreds of hours, we get a lot of those commissions,” he shares. “With qualifications only, you are swimming in a giant pool. It is hard to stand out that way.”

Once Tooza Design has secured the commission, Rob believes the process of integrating art into the architecture must be both pragmatic and conceptual. Depending on the type of installation, this can involve details that many artists aren’t tuned into. Details like footings, the plumbing lines under a building, electrical interface and structural capacity need to be coordinated closely with engineers. “If something goes awry, it comes out of your pocket. It is much better to spend time and money on your art, rather than tearing out a footing,” explains Rob. He’s found that most architects are very accommodating when asked for a model of the building done in Sketch-Up or Revit.

Aesthetically, Rob and Shelley look for ways to integrate the art into the architecture. The two ask, “What is the concept? What is important? What is going to be compatible?” The two are always looking at the material. “Art has a much broader definition now than it did when public art was paintings for the walls or a commemorative bronze sculpture,” says Rob. “We look for opportunities where someone can walk around and through under.”

And then there is the question of how safe art should be — and if an element of controversy doesn’t actually make the art engaging, exciting — and by association, successful. Rob notes, “Not everybody is going to love it, but it should not just be functional, it should have a soul.”

Nancy Boskoff remembered a series of artist-designed benches in Sugar House. One Friday afternoon Nancy received a call from a Sugarhouse resident who shared she didn’t like the project. All of her points were good ones. “I told her I’d been waiting for her call,” recounts Nancy. The resident curiously asked Nancy what she meant. “I told her not everyone can like every public art project, and I was glad to hear her thoughts.”

Some of this art will outlast the architecture. After all, paintings and sculpture, even murals and water features can be moved easier than foundations. Aging buildings will be remodeled or demolished or replaced. Parks will be replanted, and redesigned and even paved over then dug up again. But the art just might well stand as a testament to the values of the period of its creation and the community that created it.

What then is the goal of public art as a part of architecture? Is it to beautify, to express public standards, to capture the heart and soul of the of the building? To instill meaning, identity and understanding? To bring art outside of galleries and into the public eye? The answer is unequivocally yes. Perhaps, most importantly, it is a tool for social change that ignites conversations and debate. It can even become what people remember most about a place. Think of Stephen Kesler’s Whale two blocks east of Salt Lake City’s 9th and 9th intersection.

- Some Modernists considered ornamentation decadent; Adolf Loos – 1908 essay and lecture “Ornament and Crime.”

- Monument Lab (https://monumentlab.com) is a nonprofit in Philadelphia that is doing substantial work helping people across the country to sort out and deal with art that in present days has become “charged.”