Excerpted from Utah Historic Quarterly, Volume 90, No. 3

Brenda Scheer wrote a comprehensive article on the Mormon pioneers’ planning of Salt Lake City for Utah Historic Quarterly. Because of the length of the original, the following is excerpted from the original with her permission. You can read this article by subscribing to history.utah.gov/utah-historical-quarterly.

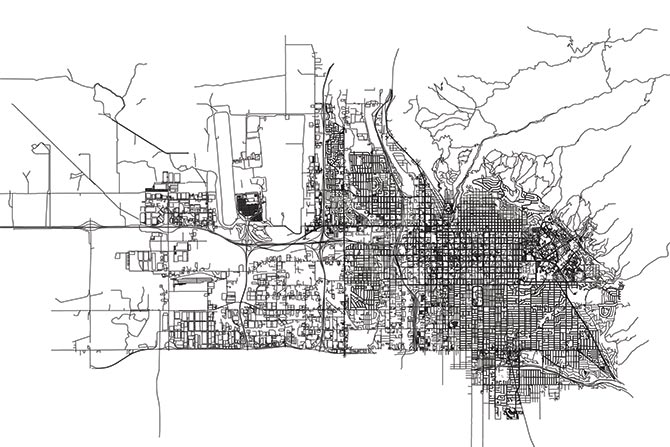

Salt Lake City has one of the most unique origin stories of any city in the United States. Not only is the story unusual and well documented, but the plan and layout of the city remain one of a kind. Any observant visitor will note the unusual width of the streets and sometimes hear the persistent myth, attributed to Brigham Young, that they were designed to be large enough to turn around a team of oxen.1 But Salt Lake City has many other unique qualities in its physical plan, which are hard to discover without research. These include its vast extent, the very large blocks, and the very large initial lots, which were driven by religious intentions as well as the model of the Plat of Zion.

The origins of Salt Lake City date to 1847 with the arrival of a small band of pioneers led by Brigham Young in the Salt Lake Valley. There, in isolation from their detractors, pioneers of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) laid out a beautiful city “foursquare” to the world. It was to be a righteous place to invite the “gathering” of the faithful from all over the world in the last (latter) days before the second coming of Christ.2

The geographical calling of the Latter‑day Saints had been the establishment of a place they called the “City of Zion,” a concept that was both physical and metaphysical. Zion was to be the center of a series of cities and villages organized as righteous and wholesome places where the Saints could live out the principles of their faith.3

The location in the mountain west was a spiritual compromise. Although Smith had located the City of Zion very specifically in Independence, Missouri, by divine revelation, the Saints were unable to settle there, due to the violence that frequently erupted when they encountered more traditional Christian settlers. After Smith was murdered by a mob, the Saints, then located in Illinois, determined to find a safer venue for Zion. The highly isolated territory on the western frontier became a suitable alternative to gather the faithful and organize a settlement system. The initial difficulty of reaching the location and its ecological hostility to settlement (a high desert) formed a layer of protection for the persecuted Mormons. It also required that pioneers were reliant on and bound to their community, with little support or trade with the outside world.

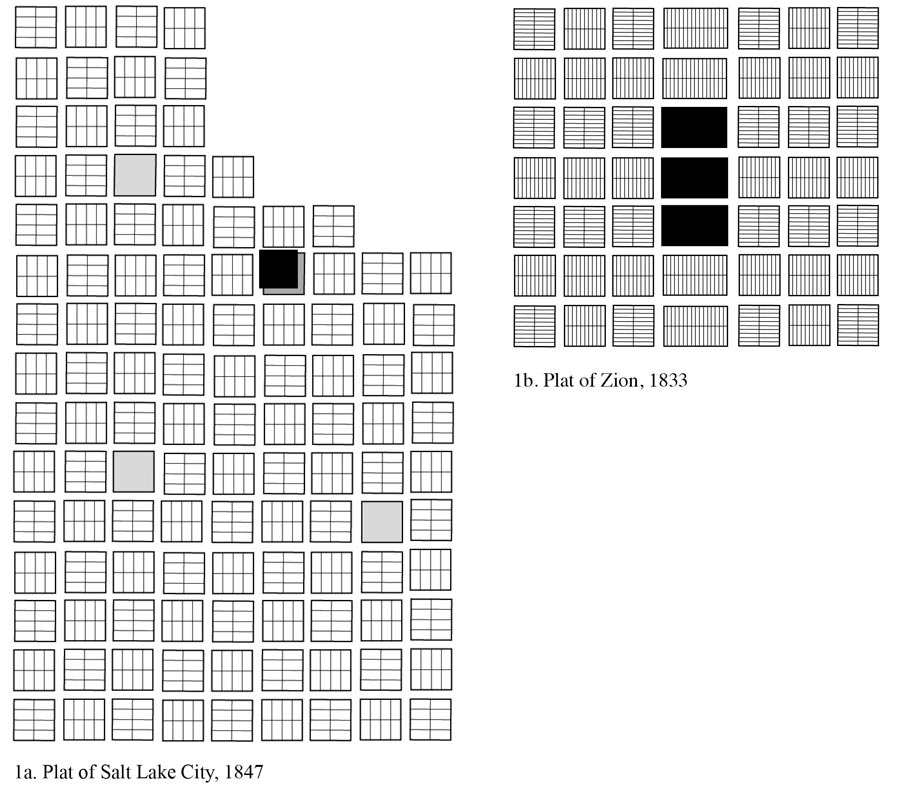

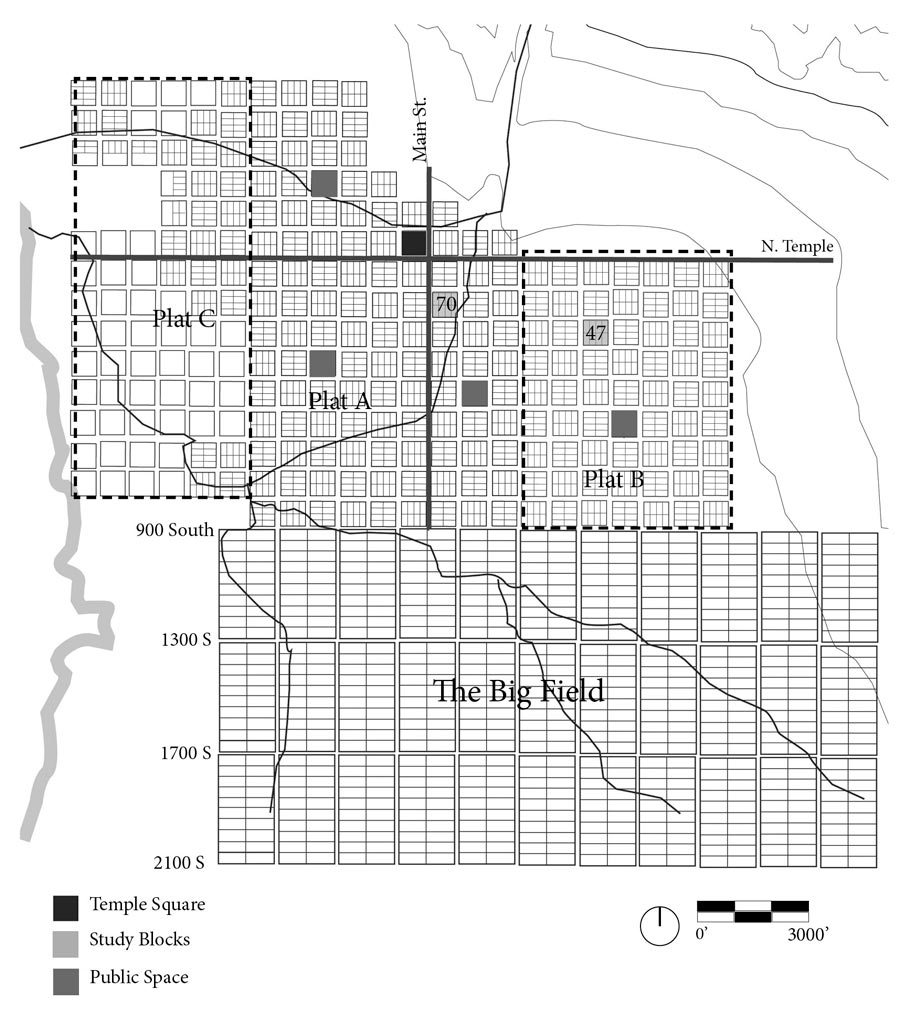

When the earliest pioneers and their leader Brigham Young arrived at the edge of the Salt Lake Valley in July 1847, they lost no time in establishing a settlement. Within days they had scouted the land for miles around and identified a place for their new city, laying out first Temple Square and then another 134 blocks in a 9 by 15 grid, oriented along the cardinal directions (Fig. 1a). The primary influence of the grid design was the “Plat of Zion” (Fig. 1b), an ideal plan for a mile-square city of 20,000 residents, drawn 14 years earlier under the supervision of Joseph Smith and intended for Missouri.4

Plat of Salt Lake vs Plat of Zion

The plan set the dimensions and orientation of blocks, streets and lots, and a central location for temples and other public buildings, but no commercial streets. Smith’s “Plat of Zion” was designed to be compact and dense, with small town lots, closely surrounded by agricultural fields that were meant for a daily commute. Smith had designed the City of Zion to hold up to 20,000 people on just one square mile, a density that would require 10 to 12 residents for every half-acre house lot.

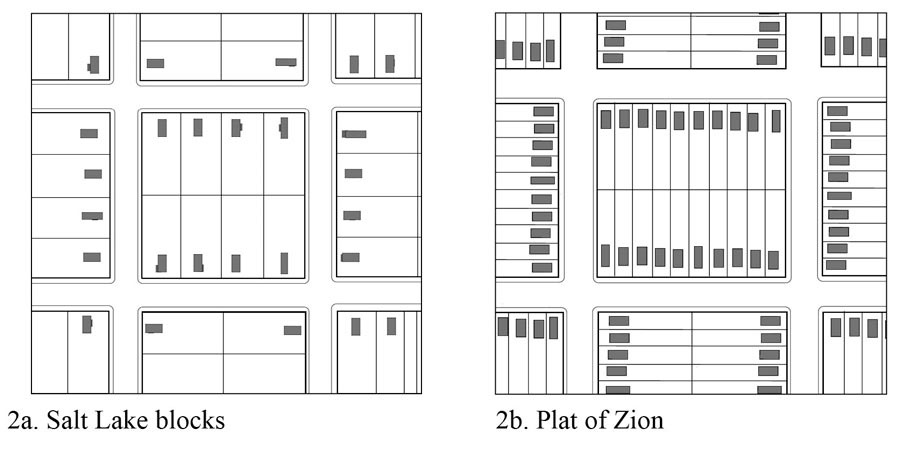

At the time Salt Lake City was founded, there were about 17,000 Mormons waiting beyond the Rocky Mountains to follow Young into the Great Basin. Had Young followed the compact Plat of Zion plan, most of them would have been accommodated in the city proper. Instead, the first plat (Plat A) of Salt Lake City was 2.5 square miles, instead of one, but was planned with only 1,080 lots. Plats B and C were laid out the following year. Young greatly altered the dimensions of the lots in the Plat of Zion to reduce the density of the settlement, which would allow more agricultural uses in town. He kept the large dimensions of the blocks and streets but divided the 10-acre blocks into much larger lots (eight instead of 20) so that each lot was 1.25 acres. This turned out to be a crucial decision. Figure 2 compares the size of blocks and lots in the initial plat of Salt Lake City to the Plat of Zion.

In the Plat of Zion, Temple Square was to be located in the center of town. Due to the topography of Salt Lake City, however, Temple Square was not geographically at the center but on the far north where the valley floor meets the foothills to the north and where City Creek divided into two streams. This is apparent on what is believed to be the initial surveyors’ working sheepskin document, recently acquired by the Library of Congress after years of languishing in the attic of a pioneer’s descendant.7 Initially, 40 acres (four blocks) were reserved for the temple, storehouses and other public use. This was quickly scaled back to one city block.5

Plat A is a uniform grid of 660 ft by 660 ft blocks (40 rods). Streets, including 20 feet set out for sidewalks on both sides, are 132 feet wide (eight rods). (The street widths were designed to follow the Plat of Zion and not for turning oxen, though the latter was perhaps a practical consequence of the design.) Each block was initially subdivided into eight equally sized lots of 1.25 acres, which is unusually large for a western settlement.6

In Salt Lake City, city founders prized self-sufficiency, permitting the planting of vegetable gardens and fruit trees in the early years and erecting barns and animal holding areas, which was a departure from the Plat of Zion directives. As planned, the lots were to contain a single house centered on the lot and set back a uniform distance of 20 feet from the street. Very early regulations also called for shade trees to be planted along the frontage of all lots.7

Plat A allocated three blocks as open spaces, subsequently developed as West High School, Pioneer Park and Washington Square, the location of the city and county building. These may have been inspired by the squares in William Penn’s plan of Philadelphia, which was an important influence on town planning in the United States.

In addition to the unusually large dimensions of the blocks and the lots, another remarkable characteristic of the plan is the orientation of the lots. Similar to the original Plat of Zion, the lots were oriented in different directions on every block, creating a basket weave pattern. The intention was privacy for the inhabitants, so that instead of houses facing each other across the street they would face their side yards, presumably planted in garden, providing a green aspect.8

After the initial 135 blocks were laid off and distributed, rapid immigration caused two more large plats — Plat B (1848, 64 blocks) and Plat C (1849, 85 blocks) — to be developed in the same pattern.9 In addition to town lots, large agricultural lots (the “Big Field”) were laid out to the south and west, fulfilling the notion of the agricultural village. Salt Lake City’s big fields consisted of five-acre allotments within a large 40-acre block. To the south, it was located between 900 South and 2100 South in present-day Salt Lake City. Figure 3 is a map showing the first three plats and the Big Field to the south, as they existed in about 1855. The initial street plan of the Big Field is reflected in the present-day location of through streets in the Sugar House and Liberty Wells neighborhoods.

The Salt Lake City plat lost cohesion from the very beginning. Instead of small houses on large lots surrounded by orchards and barns, the center of the city became urban within a few years, with small lots and multi-story buildings. Certain other plan adaptations began to take shape here that would be constant in all the Mormon blocks, although the areas outside downtown were not as dense. It was necessary from the very beginning to adapt the eight-lot block configuration, because the rapid growth of the city required far more house lots than originally planned.

In the 1870s the church’s grip on the city’s development was weakened with the influx of new arrivals brought by the transcontinental railroad and mining and commercial opportunities.10 At the same time, the emigration of religious settlers began to wane as church leaders downplayed the “gathering.” Consequently, the city began to accommodate its layout to new peoples and urban uses.

By 1889, there was adaptation in all but a few of the Plat B blocks — the subdivision of the outside four lots into many smaller lots, defeating the intended opposite orientation in the original design. These new smaller lots were far closer to standard city lots of the era, although still developed as single-family homes, not the urban rowhouses common for U.S. cities. The lots subdivided in this manner had greatly varying widths and sizes with new houses built in different styles after the lot was divided off by its owner. Despite regulation, uniform setbacks were not observed. This left much unusable land for urban development in the inside of a block. In subsequent decades, beginning no later than 1911, this problem was handily solved by creating what could be termed “mews” — short dead-end streets with small houses on either side, all within a single original lot. There are many examples of these alleys or mews in the historic plats of Salt Lake City, almost all of them surviving into the late 20th century and many still extant.

In the 20th century, the automobile began to dominate urban form everywhere. In the Mormon blocks, surface parking areas were often created in the center of the blocks. About the same time, some older houses were destroyed to make way for larger, non‑residential uses and apartment blocks, also using the vast interior of the block as parking. Scattered retail strip centers also replaced houses. Many of the smaller, less well-built houses on mews were also destroyed, consolidating lots for larger 20th century uses.

Even in 1847, it should have been clear to Brigham Young and the early pioneers that the large size of the blocks was unworkable for a city destined to be more than an agricultural village of several hundred. Making do with the size of the lots as given, further subdivisions were common even in the first allotments, despite Young’s directive to keep the lots whole. Although the agricultural village concept was successful in much smaller towns across Utah, at least in the 19th century, Salt Lake City quickly developed into a dense urban area.11

Furthermore, the pioneers had prior experience of town planning in Nauvoo, where the initial platted lots were smaller, as were the blocks and streets. Even these smaller lots were frequently subdivided in the few years that Nauvoo grew into a thriving city. Young himself had visited England and New York City and understood the nature of towns and cities. Joseph Smith greatly admired New York, passed through Cincinnati in the 1830s, and apparently was acutely interested in the creation of a great city.12

The Salt Lake City founders’ persistence in the overly generous and unworkable street, block and lot dimensions is puzzling under these circumstances.

The Plat of Zion remains an ideal vision, a compact city surrounded by green fields, all in service to a notion of a close community based on a religiously inspired work ethic, moral code and communal economy. One might also add that, by modern standards, it would also be a sustainable community: walkable, green, self-sufficient and dense. But creating the ideal central place of Zion clashed with the immediate and pressing need to accommodate thousands of new residents. The large lots of an agricultural village were never suitable for either purpose, being perhaps a remnant of Young’s own discomfort with urbanity.

Had Brigham Young actually used the Plat of Zion lot dimensions, there would probably have been more orderly development, since those lots were more in keeping with the cottages of the mid‑19th century. We cannot know. Instead, in the Salt Lake City plats, the initial lots were much too large, initiating a frenzy of irregular subdivision that created the internal small streets and irregular buildings of multiple sizes, land uses and orientation. And because the initial development was not very dense, the extent of the new city had to be expanded dramatically in response to immigration.

But it has come to pass that what may have been an ill adaptation in the city’s first century and a half may now be called advantageous in certain respects. The unique plan of Salt Lake City offers both flexibility and possibility within its rigid and enormous extent. The blocks and small alleys easily accommodate the tremendous growth in the 21st century. The wide streets have proven adaptable to a range of multiple public uses, and more may evolve to make the place a walkable, attractive environment. Salt Lake City is a very young city in the scheme of things and its evolution is only beginning. On the whole, the plan has offered what all good plans do: a sound framework to guide the evolution of an interesting and varied place.

- The idea that the city’s street width was related to turning either oxen teams or horse teams is not substantiated in the historical record but likely persists because residents (then and now) need an answer to inquiries about the wide streets.

- Steve Olsen, The Mormon Ideology of Place: Cosmic Symbolism of the City of Zion, 1830–1846 (Provo, UT: BYU Press and the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Latter Day Saint History, 2002).

- Martha Bradley Evans, “Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities,” Utah Historical Quarterly 89 (Winter 2021): 63–78; C. Mark Hamilton, Nineteenth-Century Mormon Architecture and City Planning (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 13–14.

- “Plat of the City of Zion, circa Early June–25 June 1833,” p. [1], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/plat-of-the-city-of-zion-circa-early-june-25-june -1833/1.

- Richard H. Jackson, “The Mormon Village: Genesis and Antecedents of the City of Zion Plan,” BYU Studies Quarterly 17, no. 2 (1977): 6.

- Jackson, 10.

- Stephen William Schuster, “The Evolution of Mormon City Planning and Salt Lake City, Utah, 1833–1877” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 1967), 89.

- Marilyn Reed Travis, “Social Stratification and the Dissolution of the City of Zion in Salt Lake City, 1847–1880” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 1995).

- Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom.

- Marilyn Reed Travis, “Social Stratification and the Dissolution of the City of Zion in Salt Lake City, 1847– 1880” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 1995).

- Lowry Nelson, The Mormon Village (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1952).

- Richard L. Bushman, Making Space for the Mormons: Ideas of Sacred Geography in Joseph Smith’s America, vol. 2 in the Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lecture Series (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 1997), 9.