If we put our minds (and pens) to it, AIA Utah can accomplish so much for our fair city.

Like many American cities during the postwar Baby Boom, Salt Lake City experienced serious growing pains in the 1950s and 60s. As families got larger and larger, the American Dream picked up from its urban roots and moved out to the suburbs, aided by the availability of newly constructed tract housing with big green lawns and a car parked in every driveway.

As Salt Lakers abandoned downtown apartments and dense bungalows for greener pastures, the shopping, entertainment and eventually offices followed them into the periphery, leaving a central business district that was becoming less and less viable as a commercial center for the Intermountain West.

By 1962, the situation was getting dire and — recognizing a drastic change was needed — downtown business leaders formed a group to study the issue of sprawl and come up with actionable solutions to help bring people (and their money) back into the heart of Salt Lake City. They called themselves Downtown Planning Association Inc. and were led by Jim Hogle (real estate developer and zoo benefactor), Wendell B. Mendenhall (head of LDS Church Building Department), John Krier (Intermountain Theaters and Salt Lake Chamber) and Stanford P. Darger (businessman and Salt Lake Chamber). The board of directors included recognizable names like Henry Dinwoody (furniture mogul), George Eccles (First Security Bank and philanthropist), J. Bracken Lee (former governor, then mayor) and David O. McKay (president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).

While this illustrious group representing the major downtown interests undoubtedly understood the issues as well as anyone, they needed partners who could get the plan on paper and excite the populace about funding large public works projects to propel Salt Lake City into a new era of prosperity. That is where the Utah Chapter of the American Institute of Architects came in.

AIA Utah members ended up donating over $100,000 (over $1 million in 2024 currency) worth of professional time to help brainstorm and envision ideas for a rejuvenated downtown, and they ended up getting twin billing on what became the Second Century Plan when the report was published on Sept. 19, 1962.

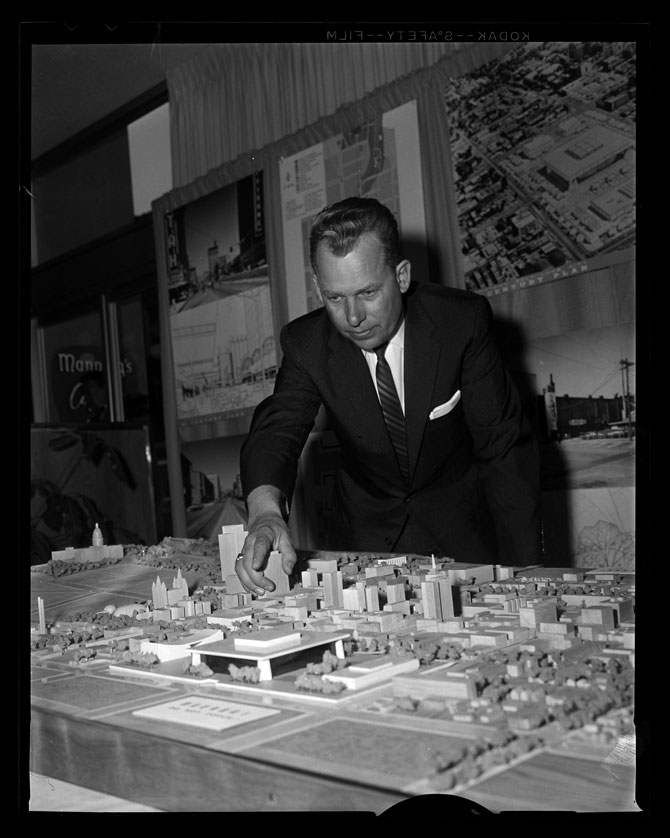

Dean Gustavson, FAIA, led the design effort as the chairman of the Development Plan Committee (DPC). A native Salt Laker, Gustavson was a World War II pilot before studying architecture at UC-Berkeley and returning to Utah to start Gustavson Associates. Gustavson’s mastery of modernist design is still evident in the Merrill Engineering Building at the University of Utah, among many other masterworks.

Donald Panushka, FAIA, served as vice chair for the DPC. Panushka attended MIT after serving in the army during World War II, then ended up in Utah in 1953, starting his own firm. Panushka was one of Roger Bailey’s early faculty members at the College of Architecture and Planning at the University of Utah.

Richard Stringham, AIA, who was a member of the first graduating architecture class at the University of Utah in 1952, was the secretary for the DPC. He started Carpenter Stringham Architects in 1956, which went on to design the George S. Eccles Building at Utah State University, the Fletcher Physics Building at the University of Utah and the North Visitor Center on Temple Square.

The DPC was rounded out by a who’s who of modernist masters, entering the primes of their careers in the early 1960s, including Martin Brixen, John Sugden, Wm. Rowe Smith, George Cannon Young and R. Lloyd Snedaker. The impact these architects had on Salt Lake and, more broadly, Utah is still felt today.

This diverse group of business owners, church leaders, architects, urban planners, politicians and philanthropists joined forces to produce the Second Century Plan, which laid bare the issues facing Salt Lake City right away in the preface:

“Downtown is the ‘heart’ of the Intermountain empire, of our state, our county, our city. It is the center of business, financial, retail, cultural and religious activities.

“Salt Lake City is one of the few cities in America built originally from a plan, thus having a better basis for our Second Century growth than is found in most cities. As our downtown enters its Second Century, however, problems common to most large cities have appeared — lack of general guidelines for growth, transportation and parking problems, a loss of much of its attractiveness, and an overall decrease in its position as the heart of the rapidly growing metropolitan area.”

The meat of the Second Century Plan started with a topic that was particularly hot at the time: transportation. I-15 was under construction and presented a new frontier in personal travel along the Wasatch Front. The vast streetcar network that was housed at Trolley Square had been replaced by buses. Meanwhile, “Circulation within the downtown [was] difficult, especially for the pedestrian. The strung-out nature of the hardcore and the extremely wide streets [made] it virtually impossible for people to get everywhere they [wanted] within the core without driving.”

The implemented solutions to some of these transportation-related issues are still evident in the city today: using 500 and 600 South as one-way “bypass routes” to get cars across town rapidly, mid-block crossings and development, and overhaul of Main Street. Some were proposed but not realized, including a free 8-15 passenger bus that would circuit between the Capitol, Sears, Farmers’ Market and large multifamily downtown developments (although UTA’s “free fare zone” comes close in spirit).

With a strategy in place for getting people into and around downtown, the Second Century Plan — led by AIA Utah members — proposed a series of construction projects for these people to enjoy and help spur an economic revival. The main projects outlined in the report included:

- Main Street Improvements: Limit automobile traffic and give pedestrians the right-of-way to promote retail businesses along the sidewalk. Largely implemented.

- State Street Improvements: Install covered mid-block crossings and tree-lined boulevards. Crossings were built, although the project of beautifying State Street is currently an urban priority.

- Block Interior: Create interior pedestrian plazas to capitalize on Salt Lake City’s large blocks. Realized over time, such as Regent Street.

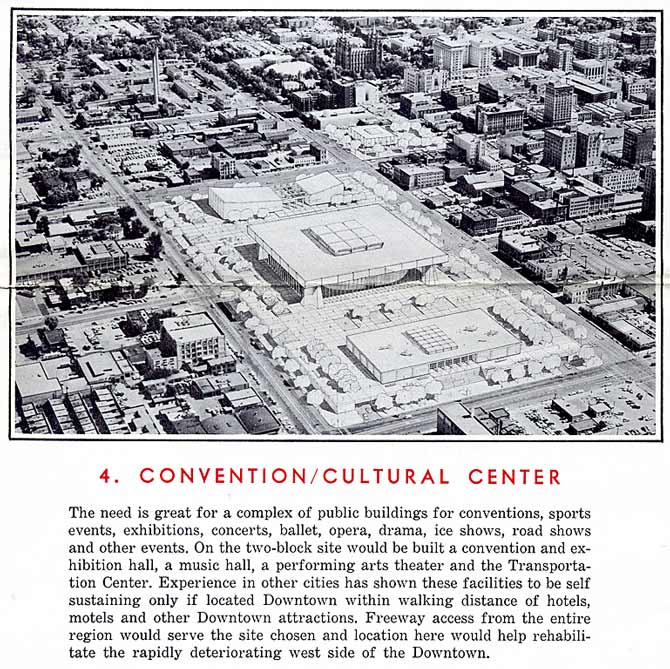

- Convention/Cultural Center: Centered around the Salt Palace.

- Visitor Center: Meant to be close to all of the tourist-oriented developments, including the Convention Center, Temple Square and hotels.

- Art Museum and Gallery: Architectural rendering depicted a Lincoln Center inspired New Formalist museum at the head of 200 East (longtime parking lot, current location of Brigham Apartments).

- Memory Grove Cultural Area: Extending Memory Grove along City Creek to State Street (currently City Creek Park).

- Farmers’ Market: This was meant to be a covered indoor/outdoor market located downtown, emulating the Los Angeles Farmers’ Market.

- LDS Church Improvements: Work on the east block of Temple Square was ongoing at the time, including closure of Main Street and construction of the Church Office Building.

- City-County Government Center: The Metropolitan House of Justice (since demolished for the new Central Library), Main Library (now the Leonardo Museum) and Courts Building were under construction at the time.

(The maps and renderings of these proposals are fantastic in their own right and available to view online through the Marriott Library Digital Collections at the University of Utah.)

While only some of the projects were built immediately following the Second Century Plan, it is hard to not see the project as a smashing success. Not only was Downtown Planning Association Inc. created as a part of the efforts (now known as Downtown Alliance), but people did start coming back into the city center for commerce (City Creek Mall), entertainment (the Salt Palace then Delta Center), culture (Abravanel Hall, rejuvenated Capitol Theatre, Eccles Theater), government services (restored City and County Building), religion (revitalized Temple Square and Conference Center), and work (the continually rising skyline of Grade A offices). Even the midcentury flight to the suburbs is reversing, as evidenced by tower cranes building the Astra Tower, Liberty SKY and The Worthington. As outlined in the Downtown Alliance’s Downtown SLC Benchmark Report, residents in the downtown are projected to increase from 14,500 in 2020 to 21,200 in 2025 and 27,000 in 2030, essentially doubling the downtown population in a decade.

Of course, this explosive growth has come at a cost. The business owners at the heart of the Second Century Plan did not consult Japantown residents before decimating their neighborhood to build the Salt Palace. The destruction of the Weir-Cosgriff Mansion and other grand mansions along South Temple spurred the Utah Heritage Foundation (now Preservation Utah) into action. Rising housing costs have created a huge gap in wealth distribution and access to housing anywhere close to downtown.

But the Second Century Plan — in all of its ambition and optimism — shows the power of our profession and our organization. If we put our minds (and pens) to it, AIA Utah can accomplish so much for our fair city.