This paper has been divided into two parts, the second part of which appears below. The first part was printed in the last issue of this magazine. The paper describes how growing evidence and research on the multidisciplinary realm of illusions of nature is giving weight to a new field of Cognitive Biophilia and Neuroaesthetics.

To read the first part, please scan the QR code: https://reflexion.thenewslinkgroup.org/total-recall-cognitive-biophilia-and-the-restorative-impact-of-perceived-open-space-part-1/

Can our understanding of cognitive function, as it relates to our sense of space, and the malleability of our body schema, as it relates to our surroundings, give rise to a new technology of cognitive design? Could these fundamental insights into the effects of spatial polarity on cognitive perception shed light on a new design framework? It is believed so.

If we account for how our neurophysiology responds to perceived open space, then we can also, to an extent, modulate the occupant’s subjective relationship with time, which, in turn, affects his or her productivity, work satisfaction and health. However, considering the inexorable trend toward large-scale, commercial architecture with their enclosed spaces – particularly in larger cities, where higher population density makes wide-open spaces a scarce resource – architects and designers are challenged to offer occupants the restorative benefits of vast, natural spaces without the physical space to do so.

Where will the architect and designer find the space needed to foster ideal cognitive function? To answer this, we must change the lens through which we frame the problem of space or lack thereof. Rather than search outward, this new design framework must be found where spatial cognition emerges: within the brain.

Cognitive Biophilia and the Impact of Perceived Open Space

In any environment – natural or artificial, exterior or interior – the zenith, the point in the celestial sphere directly above the observer, and the horizon line, the apparent junction of earth and sky, serve as environmental anchors that shape our experience of space. We must not underestimate the importance of these anchors as visual inputs that structure the spatial awareness essential to our well-being.

Multisensory Open Sky Compositions engage spatial cognition. © 2018 Sky Factory.

Architectural scholar Harry Francis Mallgrave notes that our experience of space is immediate and visceral, born of an emotional engagement that is precognitive and largely nonconscious. In his essay, “What designers can learn from the contemporary biological sciences” (included in the book, Mind in Architecture), he underscores that newer emotional models recognize that “our emotional responses are strongly integrated with our peripheral autonomic nervous system – that is, the working of our sympathetic and parasympathetic subsystems.”9

He goes on to explain that “these subsystems, in turn, are separately wired into the insular cortices in each hemisphere of the brain (a cortical region behind each ear, yet tucked towards the center of the brain). The sympathetic subsystem terminates in the right insula, which is associated with energy expenditure and arousal, while the parasympathetic subsystem terminates in the left insula and is responsive to energy nourishment, relaxation and affiliative emotions.”

This neurobiological insight reveals the pre-eminence of our “gut response” to space. Our emotional response is directly wired not just to focused vision, which accounts for a mere 5% of our entire visual field, but also to our peripheral vision, which encompasses 95% of our field of view. In other words, we perceive the general ambiance of any environment through the impact it has on our peripheral vision, which is also tied to our ingrained sense of safety or peril.

When we sit at our desks, for example, we remain aware of the space around us. We can sense when someone enters the room or leaves the door ajar. We’re aware of the ceiling and whether the ceiling fan suddenly spins faster or slower. We’re even aware, at the edge of our peripheral vision, when a spider crawls down the wall.

Peripheral vision builds our emotional connection to place. Photo by Hans Solcer, Getty Images.

Furthermore, the emotional imprint that a given space creates is converted from chemical and electrical signals into a three-dimensional map etched into our neural networks as a spatial reference frame. Architects and designers should note that these spatial reference frames, which make up our sense of space, can be evoked by recreating the contextual or environmental cues that gave rise to the original memory map or experience.

According to Dr. Groh, it turns out that “not only is memory an integral part of building a sense of space but space, in turn, serves as a kind of filing system for storing and accessing memories. And the brain’s memory-space connection relies on shared neural infrastructure.”10

This insight provides one of the clues that may answer the mystery behind why optical illusions differ from standard imagery. Unlike representational imagery, illusions are multisensory. They’re not only visual, but they also include spatial information – the spatial reference frame – that, when woven into the architectural context of an isolated interior, allows the cues to create a credible illusion of volume and depth. In fact, illusions of nature™ give rise to perceived open space because they engage a more sophisticated cognitive process than decorative, symbolic imagery.

When we provide a visual stimulus that mimics a spatial relationship with which we’re familiar, the brain’s sensory and motor regions react as if the original memory itself is being re-experienced. This is consistent with a facet of illusions; they’re capable of conjuring an experience when key cognitive cues emulate a genuine past experience.

Spatial reference frames: what you see, you become

Turning to environmental psychology, one of the most researched spatial relationships is prospect and refuge – a panoramic view of nature from a secure vantage point. Such a spatial reference frame is so ingrained in our neurobiology that the experience of deep relaxation it elicits can even be credibly simulated in isolated, enclosed spaces.

A multisensory Open Sky Composition is framed within a Luminous SkyCeiling. © 2018 Sky Factory.

In deep-plan buildings, occupants lose the two most biologically meaningful spatial relationships architecture can provide: a visual connection to the zenith (the sky) and the horizon line, both of which extend for miles in natural environments. Compressed spatial footprints without direct access to nature lead to cognitive drain. Occupants lose access to panoramic views of open sky or nature, and thereby lose meaningful mental restoration and physiological relaxation.

Dr. Groh notes that “some studies have shown that mentally picturing a visual stimulus elicits activity in the primary visual cortex and, furthermore, that the extent of this activity varies with the size of the object being imagined – tying it to the visual cortex map of space.”11 Her assertions provide a neurological basis to understand why natural environments have played such a fundamental role in the development of our neural circuitry and why, when our daily urban experience is one of limited built space, rather than interconnected open space, the negative consequences to our cognitive functions cannot be stressed enough.

Dr. Groh goes further, remarking that “such studies suggest that mental representations for space are not merely co-opted from the sensory and motor domains, but that those domains may, in turn, shape thinking in the abstract domain.”

She adds: “The implication of this is that perhaps many aspects of our ability to think and reason may be shaped by the nature of the neural “wetware” (pathways) that originally evolved in the context of sensory and motor processing.”12

Visual stimulus also engages the spatial maps in the visual cortex. Photo by Joshua Parle, Unsplash.

Therefore, if our brain acquired its neural complexity in direct response to the natural environment that enveloped our earlier psycho-physiological experience on Earth, it’s no wonder that our sense of time has a direct correspondence to the space we occupy.

Restoring the deep floor plate

Given the long life of our commercial building stock, multisensory illusions represent an economically viable and research-verified approach to mitigate the deleterious impact of enclosed interiors.

Multisensory illusions make it possible to simulate a perceived zenith and horizon line within limited structural space. These two fundamental biophilic spatial relationships can extend the interior zenith from the ceiling plane to a much more distant perceived zenith beyond the building’s roof while, at the same time, extend the interior horizon line from interior walls to a much more distant perceived horizon line beyond the building’s urban footprint.

Perhaps, using perceived spatial components inherent in optical illusions, we can capitalize on the cognitive malleability of our body schema to restore the wide-open, natural space that our psycho-physiology requires for optimal performance and health, despite the general spatial compression that our urban centers forecast in the next few decades.

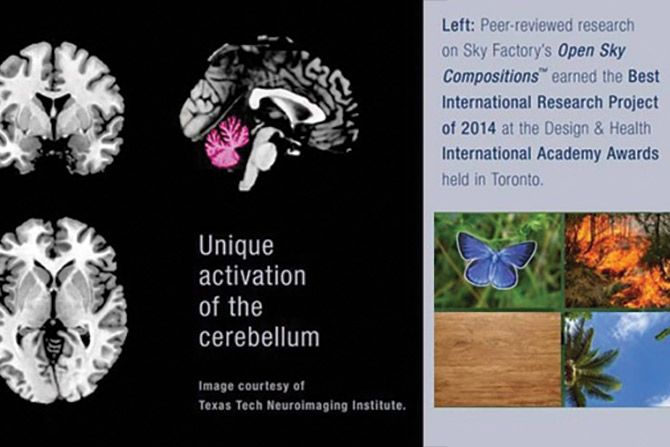

Published research on Open Sky Compositions found evidence of multisensory neural engagement.

The multidisciplinary realm of illusions of nature represents a new cognitive Biophilia. An architectural design framework based at the root of human perception would represent an advanced, research-based approach that gives weight to the restorative impact of perceived open space to mitigate the deleterious impact of buildings that will be in operation in the mid-21st century. The first signs of a rising awareness are emerging.

Among design creatives, informed clients, and commercial real estate managers, cognitive Biophilia is being used to redress the single biggest harm that deep-plan buildings affect captive populations: an absence of nature and self. In an era where staff burnout is rampant, particularly in healthcare, the urgent call to enhance occupant wellness in highly artificial and isolated interiors requires research-verified, biophilic design solutions.

Authors

David A. Navarrete is the director of research initiatives and accredited education at Sky Factory. He’s a member of The Center for Education (ACE) at the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA) and a fellow at The Centre for Conscious Design. He and Bill have co-authored articles on Cognitive Biophilia to diverse publications, including Conscious Cities Journal and Conscious Cities Anthology (2018, 2020), Radiology Today, Salus Global Journal, and Work/Design magazine.

Bill Witherspoon is the founder and Chief Designer at Sky Factory, Inc. Sky Factory’s published, peer-reviewed research has earned multiple awards, including the International Academy of Design & Health, Planetree International, and the Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA).

References (Continued From Part 1)

9 Mallgrave, Henry F (2015). What designers can learn from the contemporary biological sciences. In Robinson, S and Pallasmaa, J (eds.), Mind in Architecture. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Ch. 1, p.21.

10 Groh, J (2014). Making Space, How the Brain Knows Where Things Are. Cambridge, Massachusetts, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Ch. 9, p189.

11 Groh, J (2014). Making Space, How the Brain Knows Where Things Are. Cambridge, Massachusetts, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Ch. 9, p207.

12 Groh, J (2014). Making Space, How the Brain Knows Where Things Are. Cambridge, Massachusetts, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Ch. 9, p210.