As part of our ongoing series of interviews with architectural legends, we are proud to present this interview with long-time architect Peter Brunjes, AIA. He was gracious with his time, and it was a pleasure to interview him.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you decide to become an architect?

My dad was an architect. So, I was interested in it early on. In the 50s and 60s, I’d visit him at his office. I was always drawing and was pretty good at it.

I was born in Connecticut; my dad went to Yale. They had mostly wood and steel structures in Connecticut, but my dad wanted to study concrete which was very popular in Miami and Puerto Rico. So we ended up moving to Puerto Rico and lived there for nine years. He designed and built our home from scratch and did most of the work himself. That was fascinating.

In 1971, when it came time for college, I had two choices, go to Yale and study architecture or go visit Utah with a girlfriend’s family, go skiing, and discover Utah and its excellent architecture school. I chose Utah over Yale.

Talk about your training.

The University of Utah was really excellent. I majored in Fine Arts and Sculpture while taking basic design courses in architecture. I always went back to Chicago in the summertime, where my dad worked for Abbott Laboratories as their corporate architect. Through him, I got an insight into international architecture.

I also studied at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee my junior year; I couldn’t get the courses I needed at the University of Utah. It was a different approach than the University of Utah; I learned a lot.

When I came back to Utah to finish my senior year, I took a heavy load. I loved the idea of starting from scratch and developing a program — going through design scenarios to arrive at what was the best solution for the budget and the program — for the environment and for the engineering required.

I got married. My wife was accepted at Harvard to go into the education program. I didn’t get into Harvard, so I applied to the Boston Architecture Center. It was a good choice: it was right in town and all the courses were taught by architects practicing in the area. I learned a tremendous amount with its amazing mix of historical architecture and new buildings. I was there from ‘76 to ’78, our two sons were born during this time. I couldn’t get work in Boston, so I set off on an Amtrak pass for three weeks to look at all the different places we could live. The second stop, after Denver, was Salt Lake City. I got a job at Holland Pasker Reinhold, so we moved back to Utah.

We referred to Holland Pasker Reinhold as a sweatshop: draftspeople all lined up in a big drafting room. Cecil Holland would walk around with his pipe in his mouth and gruffly tell us, “Get back to work.” He was great. Art Pasker was very good at marketing and very connected to the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter‑day Saints; he knew a lot of people in town. I learned a lot there — a lot of detail work and production, how to produce a set of drawings and organize it, and work with consultants.

At one point, I was lent out to Ron Molen. He had two big hotel/condo jobs in Park City. It was a wholly different experience, being involved more in design and the aesthetics and the feeling of a building. The office was made of very small spaces, all of us crammed together. There was a lot of camaraderie and sharing information and experience. The fellow who sat behind me, Bob Money, had just taken the exam and passed everything his first try. Up till then, I had been hesitant. I was selling pretty well at the Park City and Utah Arts Festivals and had some shows in galleries in Park City and Salt Lake. But Bob had passed all nine sections at once, and that interested me. I hadn’t really considered becoming an architect, but it was probably a good time. So, in ‘83 I studied hard for six or eight months and took the exams and was able to get them all done in one sitting.

So, I became a licensed architect and went to my first AIA convention in San Francisco with my dad. One of the sessions was something about becoming a partner. All these young guys were saying that you basically planned your career around becoming a partner. That was news to me, but I took it to heart and set myself a goal that, in five years, I’d become a partner somewhere. That wasn’t going to happen at Ron Molen’s because he was a sole proprietor, did all the initial design, and held things pretty close to the vest.

I started looking around town and interviewed with the up-and-coming firms. I couldn’t get into Valentiner’s. I realized later that the office manager had a reputation for controlling his appointments. So, I called Niels at home. He was very understanding. We met soon thereafter, and I was hired. I was really psyched to be part of that firm. I started in ‘85 and immediately was given a project to manage by myself. I had taken projects all the way through before, but this was me with the client: find out what needed to be done, get it done.

I grew pretty quickly at Valentiner’s. FHP Medical Health Care was an insurance-based program, and they were expanding. I took that on, and we did a bunch of clinics around the area: Ogden, Provo, Salt Lake City. We did a big hospital and a specialty center in South Salt Lake for them, which later became Granite High School, that our firm remodeled into educational spaces.

In 1989, Niels said, “I’m reorganizing the firm and I’d like you and Sean Onyon to join me as partners.” I was very, very thrilled and told him, “Absolutely, I’d be glad to bring everything I have to the growth of the firm.” Soon after, he asked, “What would you think about bringing Steve Crane on as another partner?” He brought a lot of education and marketing experience to the firm. So, in 1990, we became Valentiner Crane Brunjes Onyon (VCBO).

How did your specialties develop?

I took to healthcare early on. Over the years, I pursued that kind of work at the state, the university, with Intermountain Healthcare, and with other physician groups. Then, I remember sitting in on an AIA conference where hospital administrators were presenting their side of the healthcare story. The economy and politics were hurting health care, and they had no strategy for where or how to grow.

At that point, healthcare design work was faltering, and big healthcare architecture firms around the country were working on other kinds of projects. A big practice area was correctional work. I got involved in corrections, mostly youth detention centers, and I had been involved with modularity at FHP in healthcare. It really applied to correctional work: working on modules of 8–16 beds around a dayroom. The designs had to be very functional and everything visible like in a hospital. I really enjoyed that work and hopefully contributed to a number of younger kids finding their way in life through a better facility that felt comfortable and encouraged them to be better people instead of punishing them.

One of our favorite stories of yours is Happy’s Temple. Tell us more about that.

During the late 80s and 90s, we got involved with Coca-Cola’s Park City snow sculpture contest. A group of us would get together with our kids and families and go to Park City. We piled a lot of snow by the high school and then sculpted it. Generally, I was in charge of the design and making it feasible — fun and recognizable for the crowds coming through. We also wanted to win the prize money to give away to Books for Kids. We won year after year.

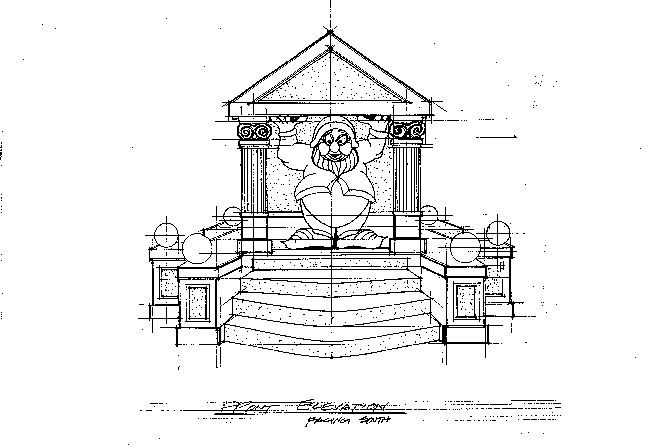

One of our best was Happy’s Temple. It was Happy, the dwarf from Snow White, in his temple that was like the Parthenon. We won the $1,000, which went to the kids. Later, we were submitting work to the AIA competition for that year’s projects. It got an honorable mention award from the AIA. That was wonderful.

Talk about some projects that you’re particularly proud of.

My favorite, early in the 2000s, was the Health Sciences Education Building at the University of Utah. We worked with so many departments at the University Health Sciences Campus and DFCM.

It was a real milestone in my career. We were working with a firm from Boston and were in charge of writing all the specifications. The Boston architect said, “What did you choose for the front door handle?” I showed him, and he said, “Well, that’s good. But that’s the first piece of the building the users will touch when they come to the building. So, we really want to make it nice and tactile.” So, we chose something even nicer in stainless steel. What’s the building really going to feel like from the very first moment somebody opens that door? That’s important. Additionally, we commissioned artwork through the Arts Council and selected three artists to provide artwork throughout the building. The team incorporated the art into the building where it really was seamless.

It was my first indication that I needed to work with an entire envelope. That added another layer of complexity to an already complex program. I went into the project knowing we must provide the client with a building that was state of the art and had a super tight envelope.

That was the first project where we followed through with LEED certification, and it was the university’s first project pursuing a LEED Gold certification. We led the client through the process, making choices based on how much it would cost, but also on what was right for the future, the users, and the environment. The project was CM/GC, so we had the contractor on board very early in the project to rely on to help make many more design decisions, like making the connection between the building and the library work and being weatherproof and functional. We watched them take on their LEED requirements: no food, drink, no smoking on campus. It really changed their culture. Imagine a building site with no Big Gulp cups! They started recycling much more of their waste — cardboard and sheetrock that they separated further and further so they could recycle it more carefully. The entire paradigm changed for contractors during this project.

Talk about changes in the industry from the 70s through to your retirement.

By the mid-80s, I had become a very good draftsperson and could get around the desk and drawing tools quickly and develop plans. But the era of CAD was starting, and that changed needed skillsets. It started with just floor plans, things that could be repeated — like different floors. Later, it became the whole set. Then Revit was another whole change. You could design everything in three dimensions!

t was wonderful for the client to see the project develop in three dimensions. Of course, there was Sketch Up and other software that enabled us to sketch buildings in three dimensions.

Sustainable design was a huge revolution. Until LEED, we were doing buildings generally that would pass silver certification. When LEED came out, I took the exam and became fascinated by the whole process of transforming: recycle, reuse and efficiencies and design for materials and where they are sourced. Envelope design became a very engineered approach for all the seams and joints and corners and roof and parapets and down at the base of the wall, taking into consideration condensation and the building needing to breathe but still be weatherproof.

That became our Holy Grail over the next few years. At first, it was a struggle getting clients on board to spend money on components of the building — LED lighting or glazing — the things that would cost more, but pay off in the long run. It didn’t take long before developers were saying, “If I spend this much more on this building, I can get this much more for rents.”

Talk to me about any disappointments you might have had.

Partnership was this bright goal when I was a young architect and it turned out very nicely. I exceeded my goals. But like with any firm, you’re dealing with egos and different personalities when you partner with people. We were very careful, the four of us, adding partners. Maybe it is growing pains, but it was a lot to manage and tempers would run thin, opinions would run hot, and that was disappointing.

But it was a business, and it was seriously run as a business. I really respect Niels for many things. One is his business sense and running the business. But getting along as partners, you’re basically married to each other. You have to respect each other. Even with the full support of the other partners and the resources of the office, sometimes you step on each other’s toes, or don’t agree with something that happens with a project. Generally, we worked everything out. We grew together and figured things out, and I think, really had a lot of respect for each other.

Advice to somebody starting out in the field?

Really get into the culture where you work. Do everything you can to contribute positively to the feeling of an office. It becomes a second family and it’s important to treat it like that. If you see a void where something’s not being taken care of, do it. If the firm needs some master planning and you can do that, or you feel you could take a stab at it, do it. Even if you’re starting off, you can still empower those around you with encouragement. As a developed architect with experience, it’s important to empower everybody on your staff. And don’t ever go backwards and put somebody down or hurt or punish anybody for doing something wrong. Just learn from your mistakes. Empower people to move forward and grow.

To watch the full interview, please click the link.