How might one analyze older photographs of Utah — downtown Salt Lake City in particular — to gain some knowledge about little moments in life as they were lived in another era? Is it even possible to ascertain such a thing with any detail by examining, studying, and researching what is captured in one or two old black and white photographic images or surviving local primary sources like newspapers?

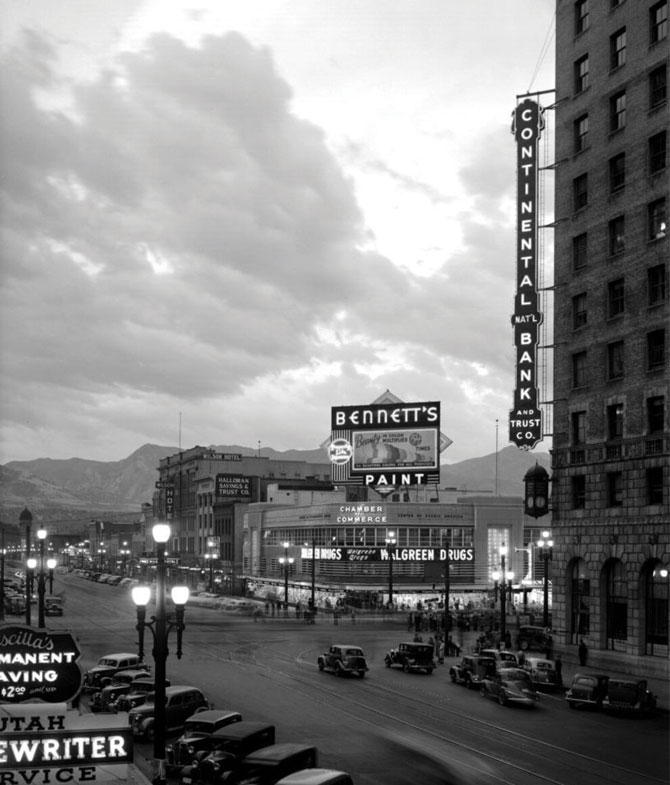

Two key questions that one should pose are the following: when, precisely, were the photographs taken, and what do they most prominently depict or capture? For example, let us consider and analyze two superbly detailed photographs of Salt Lake City’s Main Street, both conveniently and precisely dated October 4, 1938, and both part of the Utah State Historical Society’s Clifford Bray Photograph collection, Mss C-321, Bray numbers 1307 and 1307-A. A copy print is also part of the Classified Photograph Collection, under S.L.C — Main Street-II p.156 No.26350 — but that one lacks the clarity of the original negatives.

One Bray image, 1307, was photographed about eight minutes before the other one, 1307-A. How can this level of detail be ascertained? The outdoor multi-clock apparatus or cupola in photo #1307 has the west-facing clock hands pointing to 5:57 p.m. (see the image above), and that same clock apparatus in photo #1307-A has the clock pointing to almost exactly 6:05 p.m. Unless the clock mechanisms stopped working, the times the hands indicate should be accurate. Unfortunately, this curiosity of clocks no longer exists on the exterior of this building.

And what day of the week was this? It was a Tuesday, according to the perpetual calendar. The time is almost close to dusk, and the two moments captured in the two photographs were about an hour before that time. As an example, moving closer to the present day, on October 4, 2019, sunset in Utah was approximately 7:03 p.m.

Looking more precisely at the centerpiece building in the images, and its early history, is one way to approach the images with a more detailed focus. The tall building in the right foreground is quite prominent in the image, but the two-to-three-story-looking-one in the center is the one most prominently captured, or the focal point. Indeed, from my perspective, the centerpiece of both images is almost precisely in the center — a then-new commercial building that housed a Walgreen Drugs store: the Salisbury building.

The Salisbury Building was on the intersection’s southeast corner. The other major building captured in the images is the Continental National Bank and Trust Company building, on the southwest corner of the intersection 200 South and Main Street. It still exists as the Hotel Monaco. These two exterior images were taken just over a year and a half after the Salisbury Building witnessed its own grand opening to the public with much publicity and fanfare.

Old Utah newspapers, especially those that were published in Salt Lake City, are the best sources to resurrect the details of this building’s initial or early history, when it was brand new and a powerful symbol of consumerism to the local metropolitan populace. Indeed, a somewhat forgotten local newspaper, the Salt Lake Telegram, provides a great deal of detail about the then-new Salisbury Building as it wandered on its path to construction and a grand opening in late February 1936.

The old Kenyon Hotel, built in the early 1900s, and a prominent Salt Lake City building landmark, was demolished in 1935 to make way for the new building. Our Utah State Historical Society image collections contain a few dozen exterior and interior photographs of that hotel. A May 13, 1935 article notes that the new building was supposed to be ready for occupation by January 1, 1936 — in only about ten months — and that the Kenyon Hotel had already begun to be demolished. The target date for opening ended up being late by only about a month and a half.

The Salisbury Building was part of a major increase in spending on new building construction in the city during 1935. Local labor and materials were to be used as much as possible for construction.1 Marble was also part of the construction material.2 An architect’s sketch for the coming new building that appeared in the Salt Lake Telegram on May 13, 1935 only captures some elements of the overall look of the building when it was completed. Key parts of the conception changed before construction. For example, the tower-like center section was eliminated, as well as the eight lateral protruding extensions on Main Street. See https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s61271rf/16393241.

The architect’s sketch of the coming building reflects much more of an Art Deco style, with its emphasis on vertical lines, and stylized, geometric ornamentation, rather than the Art Moderne style, with its emphasis on horizontal lines, and sleekness, a style that the building displayed when it was completed. This is indeed an interesting micro-moment or shift in architectural history, captured in the documentary record of a local city newspaper and a few Bray photographs.

A Schramm-Johnson Drug store was scheduled to move into the new Salisbury building, and the drug store was to be the largest “of its kind” in the Intermountain region. This chain of local stores was affiliated with the Walgreen Drugs Company chain. The store was planned to be four times as large as the one that previously was at the location.3

A Salt Lake Telegram article on July 18, 1935, noted that a building permit application had been filed (number 13363) for the construction of the two-story Salisbury building, to be built of brick and concrete, and that the cost of construction would be $280,000, which in today’s dollars (adjusted for inflation) would be $5,275,000.4 The permit application notes the dimensions of the building were to be 186 feet long by 141 feet wide. P. J. Walker, the general contractor, filed the application.5

The new Salisbury Building contained more than just the Walgreen Drugs store — there was also a shoe chain store called Fashion Bootery. Mr. Siegel, president of the chain, visited Salt Lake City on February 15, in preparation to open the chain’s new store, the eleventh for the chain, which had its other stores in Washington, Oregon, and California.6

The new building held its grand opening on Friday, February 21, 1936, with the Walgreen and Schramm-Johnson Drugs store as its flagship business. It was an air-conditioned building and, at that time, the largest drugstore in the entire nation. The building had three floors, which included a basement, with a second floor that was used for office space and storage space.7 An extremely large illuminated, mural map of the world rested on the main floor’s east wall. There were thirty-three dining booths that could seat one hundred sixty people. $100,000 of merchandise was available in the store for sale. The director of the Walgreen Drug(s) company, Joy H. Johnson, attended the grand opening.8

With its extensive interior neon signs, salmon-colored and buff terra cotta, and stainless steel trimming enhancing the streamlined horizontal lines, it was more than just a drug store. It was a shopping and dining mecca for the working and service classes — for in that era such stores, and especially this flagship one, were replete with a range of options more akin to a mini Fashion Place Mall. Thousands of people visited the building on its day-of-grand opening.9

Old black and white photographs, like these of the exterior of Salisbury Building, and the interior, are artifacts that capture and reveal little facets of their place in space and time, but require a little diligent research to place in a more complete context. They provide indelible insights into the history of the public social fabric of metropolitan Salt Lake City at one brief moment in time, and are a most valuable part of the Utah State Historical Society’s image collections.

About the Utah Division of State History:

In 1897, public-spirited Utahns organized the Utah State Historical Society to expand understanding of Utah’s past. Today, the Utah Division of State History administers the Society as part of its mission to preserve and share Utah’s past. The Division collects materials related to the state’s history; assists communities, agencies, and building owners with archaeological and historical resources; administers the ancient human remains program; manages a specialized research library; offers extensive online resources and grants; and administers the National Register of Historic Places. For more information, please go to history.utah.gov.

Footnotes:

1 May 1 13, 1935, Salt Lake Telegram, page 5

2 December 2 5, 1935, Salt Lake Telegram, page 24

3 May 3 16, 1935, Salt Lake Telegram, page 7, https://digitalnewspapers.org/

4 https://www.usinflationcalculator.com

5 July 5 18, 1935, Salt Lake Telegram, page 10

6 February 6 8, 1936, Salt Lake Telegram, page 2

7 February 7 20, 1936, Salt Lake Telegram, page 7

8 February 8 20, 1936, Salt Lake Telegram, page 17

9 February 9 21, 1936, Salt Lake Telegram, page 24