This is the second in a series of architectural legends; interviews with retired architects who practiced in Utah during the second half of the twentieth century. These memories archive the personal careers of these architects and speak to the evolution of the architectural industry in the United States.

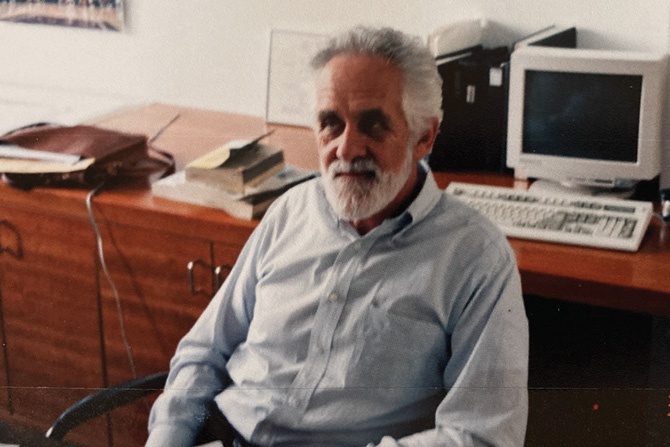

Frank Ferguson is the second “F” of the prominent architectural firm Fowler Ferguson Kingston and Ruben (FFKR). Fran Pruyn and Darby Doyle of City Home Collective spoke with the very vital Mr. Ferguson in his home in Holladay in late May 2021. He chronicled his decision to enter architecture, his education in Utah and Minnesota, his experience in Europe, the Midwest, and San Francisco, and how FFKR became an important and established firm in Salt Lake City.

When did you decide to be an architect?

I had been at the University (of Utah) in the School of Engineering, but I wasn’t measuring up; I wasn’t good at it. Then I went on a mission for the LDS Church to Canada. When I came back, I thought about it and decided I would like to be an architect. Why? Because I was right next to the art school, and the architecture program at the U had started only a few years before. Roger Baily was traveling through Salt Lake, he met with the President of the U, and they got a school going.

I had been taking watercolor classes, and I would go over there, and there would be these drawings [by] architects. I would walk away and my heart would be beating, and I’d think, “Boy, that looks great.” So, I registered in the architecture school and graduated in 1963. Roger encouraged me to go to graduate school, so I went to the University of Minnesota and graduated from the University of Minnesota in architecture after getting a degree here in architecture. It was a great time in my life. I met some great people on the faculty and the student body.

What next?

I had always been interested in Gothic Cathedrals. I wondered how in the hell did they get built. So, my wife and I decided that we would take our two kids and go to Europe. I got a job in a small town in the French Alps. It was a good firm, and one of the chief architects made it possible for me to work on a design of a Catholic Chapel in the Alps for the Olympics. So, I kind of fell into it. That is the first real design I did as a professional. The firm was just right for me, and I was just right for the firm.

Frank returned to the United States and back to Salt Lake City in the seventies. He, Ray Kingston, Jack Smith and John Perkins formed a firm called Enteleki.

John Perkins left, and Jack Smith, who was working on Snowbird, moved to Sun Valley. That left Ray and me. I was friends with Bob Fowler. We were both competing for Symphony Hall, and Bob got it. We were friends, so I wrote a letter to Bob and said, “I really feel crummy. I really wanted to have that job, but if I can’t have it, I want you to have it.” A couple weeks later, Bob asked me to come over and said, “I want you to be my design consultant,” because it had to be done in a short period of time. Bob believed in me like I believed in him. We worked side by side. He was the architect; I was his design consultant.

FFKR’s first project was Abravanel Symphony Hall for Salt Lake County.

So, we started on Symphony Hall. There was enormous pressure, but sometimes pressure helps you with the decision-making process, and your brain works better because you can’t sit around and dream about things. You have got to get things done. Without Bob, it would never have happened. It wouldn’t have been the same without me, but I had no political weight. Bob had plenty of political weight (to sell the design). All this time, we were just having a great time. It was wonderful.

The building never looked better than on opening night. Nobody had tampered with it.

How did you divide the labor? How did you choose which projects you would work on?

We were a studio. As a studio, we had a certain amount of freedom. FFKR today is a corporation. I could not survive there. A studio allows ideas to bubble up from below. Doesn’t matter who they come from; it is the best idea. When a new project would come in the office, we would assign it to one of us, and we just worked together and had very good people. We were careful that we worked hard every day and efficiently, and we were able to make our payroll. You couldn’t draw a corporate structure of either Enteleki or FFKR. It was a very artistic environment, I think, and I liked it a lot. We had a partner in charge — myself, Ray, Joe Rubin, and then we would have good people on the staff that worked with us. So, I would have my studio, my group of people, and Ray (Kingston) would have his studio and his group of people.

What are you most proud of during your career?

We were able to lift master planning out of a morass because of Jack Smith. Jack came from the East; he had a sophistication that I didn’t have. He undertook the master planning of Snowbird. I think we put master planning on a different plane, and the credit for that really goes to Jack.

All we did was try to put modern architecture in a good light. We were all trained as modernists. I don’t think an architect can be everything to everybody. I think you have to focus on what you believe in and what you want to do. I know a lot about the Bauhaus, I know a lot about the Bauhaus principles, and I put them to work in my buildings.

I have had some wonderful opportunities to put those ideas into play. The most meaningful projects: Abravanel Hall was a great experience for me. I did some stuff at BYU. The library there is buried. We said, “keep the quadrangle. Put the library below it.” I am quite proud of that building.

We did the Delta Center, it was a pretty clean glass box. We had a very clean, beautiful building. Larry (Miller) was a demanding, fair, brilliant guy. You know, you learn as you work for various people that there’s some people that you can tell once and they get it. And there are other people that never get it. He got it.

And the Jerusalem Center, and that was really wonderful. It took ten years to get that done. I was on the phone in the middle of the night talking to my Jewish partner in Jerusalem. Without him, it wouldn’t have gotten done. If you take the Jerusalem Center, the first day I walked out on the site, I was so happy I couldn’t talk.

By the way, I have never done a project where the first sketches lead to the final result. If I showed you the first sketches for the Jerusalem Center, you would be shocked. I am shocked every time I look at them because they were so wrong. But you gotta start somewhere.

Wrong in terms of what the client wanted, or wrong in terms of what the building was about?

The latter. Jewish subcontractors hired Palestinian craftsmen to build that building. I had no appreciation for that when I started on it. We finally developed a good scheme; the first scheme was terrible. I don’t think you can start with details and end up with a good building. You have to start out with a unifying concept and let the details come later.

How do you feel about the evolution of the (architectural) industry, from the sixties when you began until 2006 when you retired?

Everything I am telling you came before computers. I had a pencil and a hand, and every project on there was done with a pencil and a hand, and no Computer Assisted Design, which I recognize is a great thing, but I pre-dated that, and I honestly don’t know how I would have done.

Modern Architecture today can be horrible or it can be great, and it is both. If you look at Renzo Piano and his work, it’s great. If you look at some of this other stuff that you can see everywhere, it’s junk. And I don’t feel good about it, and I think it is because people don’t draw anymore. Now that is a very naïve opinion, but drawing helps you think, and if you are sitting in front of a screen and you are poking buttons and the button does everything for you, I think your brain tends to shrink a little. On the other hand, there are some really great buildings being built right now by people who depend on computers to do their work. I don’t know how they do it; I couldn’t. I was far too biased toward working with this guy (his hand).

What do you think is the best building in Utah?

The best building in Utah is the Capitol. Richard Kletting did a great job.

What criteria would you apply to be a “good building”?

To go into a building and know where you are, and to feel good is at the heart of it, and if you can’t do that, and there are buildings that I think you can’t do that, you have missed the point. Energy has become important, but it’s not everything. You can’t tell people to feel good because the energy bills are low. Everything is to feel good; it is to want to go back. Everything is to say, why don’t we just sit here and look at this thing. There is a wonderful addition that Renzo Piano did the Morgan Library in New York City. I could go there and just sit all day.

What makes it so wonderful?

It is full of natural light. I think natural light and the play of light across surfaces: white is never white; it is always close. Most of my buildings are transparent in one way or another. My inclination is to keep things as open as possible. I didn’t start out that way. I have learned a lot since I started in architecture. I was so naïve when I started.

How so?

Because I didn’t have any experience. I can remember a time when I would go to see potential clients, and I would say I did this job at the U and I did this project at the U in Minnesota. I had nothing to show people. Those are short meetings. But then along came a guy with Salt Lake County who believed in us, gave us a real project. There is nothing like designing something then having to build it, and like it. I have buildings that I fouled up, and I have buildings that I feel good about too.

If you were going to give advice to a young architect, what would it be?

Get out of town. My exit from Salt Lake City to the Midwest, to Europe, to San Francisco, to California. Gee, what a difference it made. You are not going to get the opportunities. I would say get out of town, somehow.

And come back?

Oh, like me, I came back. I did architecture in the Midwest for a while. Gee, I wouldn’t want to do that for a lifetime.