Jack Smith attended the University of Utah and loves art, the humanities, and philosophy. He says that it was his avid skiing that helped form key relationships: with his mentor, John Sugden; with Ted Johnson who gave him the commission to design concepts for Snowbird; with Dan Kiley, who introduced him to important projects and great talents. Ultimately, he landed in Sun Valley, where he skied, to set up an independent practice. This is the latest in AIA’s series of legendary Utah architects.

When did you decide to become an architect?

I was brought up in Provo, Utah, and my Uncle Ben was a contractor. I think my first job was straightening nails when I was about eight. In those days, during the war, you couldn’t get nails. He gave me the job of pulling and straightening nails. He could do anything. He was a craftsman, a mason, and cabinetmaker. He taught me how to frame a building when I was probably ten. So, I understood how buildings went together; I knew what a stud was, what a joist was, what a rafter was.

Tell us about your training.

In those days, at Irving Junior High School, we were in an “Articulating Unit,” seventh and eighth grades combined. Also, if you had a B average or better, you only had to take two years of high school. So, I entered college at 16. At the University of Utah in 1948, the education was both modern and classical architecture. That was a real benefit.

John Sugden, who was a skier and a climber, came to Utah. He was just out of Mies van der Rohe’s office in Chicago. He was Mies’ protege. In 1953, I became Sugden’s first employee. I left school after about four years, without getting a degree and went to work for Sugden, with whom I apprenticed for about 12 years. That training gave me a Miesian discipline, which I use today. John was a huge influence on me. And then I also was asked to teach, interestingly enough, prior to getting a degree, at the University of Utah. I taught basic design from 1964 till about 1967 when I went back East and joined Dan Kiley.

How were you invited to teach and then work in Kiley’s practice?

I was working half time with Brixen and Christopher Architects, and then half time as a teacher at the University of Utah. I was invited to come to the U of U and have lunch with Bob Bliss at the faculty club. And I said, “Well, yeah, free lunch? Sounds okay to me.” I went not even thinking that I would be asked to teach because I didn’t have a degree and I wasn’t even a licensed architect at that point, but I had been working with Sugden. So, I was talking about Josef Albers and it turns out that I was actually being interviewed. I went on and on talking about how important he was in the color world and the Bauhaus, and that they should buy this book called Interaction of Color. Then Bob said, “Well, tell us more about that.” I had no idea that Bob Bliss had been working directly under Albers and knew him pretty well. Then they just asked me if I wanted to teach and I said, “Goodness, I’ll say.”

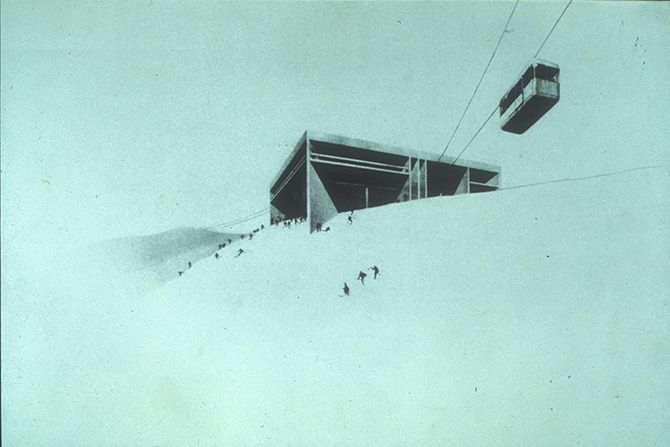

So, while all of this was going on, I also had received a commission from Ted Johnson to do Snowbird Ski Area. I was still with Brixen and Christopher as an associate, and I was also teaching with Bob Bliss. Ted Johnson had not acquired all the property yet, so I did all the concepts of Snowbird by myself in secret. I had a secret office in Sugarhouse. We had to go up on the roof and go in a window. Because it was secret, we couldn’t go in the front door.

I wanted it to be a studious modern American ski resort. Having been a skier and knowing that Sun Valley and so on are all basically about Austria or Switzerland or something in France. I said, “No, this has got to be something different from that.”

I established the concepts for Snowbird alone. Then after it really started to become open, I formed Snowbird Design Group with Marty Brixen, Jim Christopher, and Bob Bliss. Ted Johnson only had the money to acquire certain mining strips, so we had to do a limited partnership. We raised $400,000 and that gave us the money to actually design. That’s when we did the more developed ideas about Snowbird. But it still wasn’t funded. Dick Bass was the money behind Snowbird, and he didn’t come in until late ‘69.

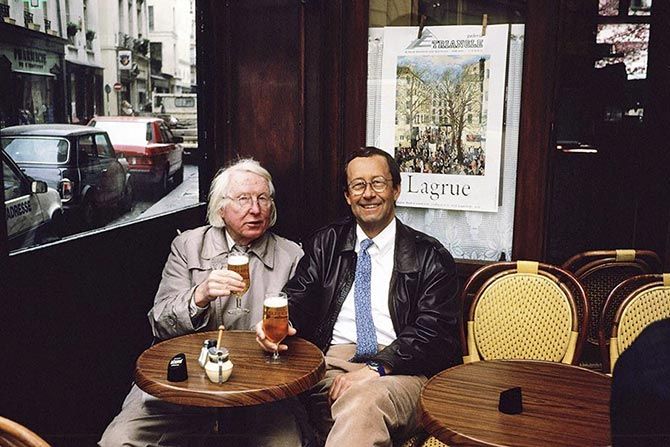

I was teaching when Dan Kiley, who was very famous, came to lecture at the school, and I was very taken by him. I asked, “Are you a skier?” He said, “Absolutely!” So, we went skiing and I showed him Snowbird, which was still in its infancy. Then Dan said, “Well, it’s not funded, why don’t you come and join me?” And whoa, having that opportunity to go join Dan Kiley, “Of course!” I went back East and was an associate the first year, then from ‘68 until about ‘71, I was a partner.

Dan Kiley was one of the most important landscape architects of the 20th Century. I spent about five years with him, and we did environmental land use studies. We also did a number of high-rise office buildings in Calgary. I went from Salt Lake City to an international practice with Dan. As his partner, I was able to be involved in really major projects. We had clients like I M Pei and Eero Saarinen: being involved and brushing shoulders with greatness, and international opportunities — work all over the world.

Then in about 1970, I was asked to go back to Snowbird and complete the work with Snowbird Design Group. I could go to Paris for three years or return to Salt Lake City to do Snowbird. Dan encouraged me to do the latter because it was kind of my baby, and so I did. I expected to be made a partner at Brixen and Christopher, but I wasn’t offered that. Since it was my job, my project, I stayed involved. Brixen and Christopher were the Architects of Record for the first phases, for the Tram, Tram Building, Lodge 1, and also the Plaza, based on the designs we did as Snowbird Design Group.

The plaza was Dan Kiley’s idea. Snowbird is a very steep runout, there’s no runout really. So, to cross the bridge, and go to a plaza and build a village on that other side was Dan’s idea. That was a very important move. The plaza is essentially the core of Snowbird. Because I wasn’t offered a partnership with Brixen and Christopher, Ted said, “Why don’t you just start your own firm?” He wanted me to complete my work. I was the author of Snowbird. So, I started Enteleki. After that point, we did all the rest of the buildings, including the Cliff Lodge. I started the firm with Ray Kingston and Frank Ferguson. Now that firm has evolved into FFKR, (Fowler Ferguson Kingston and Ruben).

In Aristotle’s de Anima there’s a word called entelechy. It means “the actualization of the potential to its nearest point of perfection without loss or compromise.” The actualization of a potential is quite different than actualizing what you’ve already seen. Essentially, you’re making something visible that was previously invisible, right? That’s a creative process.

Snowbird was done by a number of people. Our firm, Enteleki Architecture Planning Research was not vertically aligned. It was more like a really a tight little artistic studio. Lots of people were involved with Snowbird. Certainly, I was the original author for the concepts, but many other people were involved all the way through and that’s what made it successful.

When did you decide to leave Enteleki and what did you do next?

I had basically been involved with Snowbird for 10 years and was also running a firm – we went from three people to 75 people. I was president and we had an office in San Francisco as well as Salt Lake City. I was living on an airplane, which I had been doing with Kiley for years. I wanted to really get a little bit more involved in my own work. So, I left Enteleki and started my own firm called Jack Smith Architect. I moved to Sun Valley, where I’ve had an independent practice since.

That leads us to the academic side. I taught at the University of Utah, and I taught at the University of Idaho in Moscow for a semester. I was a distinguished practitioner in residence for a year. I think right now I’m still an affiliate professor.

I went back to school at age 68 or 69, to the University of Hawaii for two reasons: I wanted to dig deeper into what Architecture really means, and I wanted to teach more. I spent five years to get a doctorate degree. Because I was already an architect and also a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, and had won a lot of design awards, it was not necessary for me to be involved in the school of architecture so much. They said, “What do you really want to do?” I essentially designed my own curriculum for a Doctorate of Architecture. I was in the philosophy department. My professors were from Japan, India, China, and Oxford University. I’m not a philosopher as such an armchair philosopher, but I have five years of exposure to philosophy at a doctorate level.

That led me to Montana State University. I didn’t expect to teach there. I was doing a large ranch that was near Bozeman. I visited the school just for fun. But they offered me a full professorship, and I couldn’t refuse it. I thought I’d stay there for a semester or two. I stayed there for 14 years. I only retired from teaching in 2020 and returned to practice full time. I’m not going to quit. You know, I think retirement is a disease.

The interaction with student/faculty interaction keeps you sharp on all levels. You’ve got this symbiotic relationship between teaching and practice. The interaction with students is heaven. You fall in love with them. They’re your children. I get letters now clear back from the students I had in the sixties. It’s amazing.

What is your philosophy of architecture?

Architecture must first be thought of as an art form. There are three levels of comfort. The first level is to make a physically comfortable building. Is it warm in the winter? Is it cool in the summer? Is it going to stand up? That’s just physical comfort, that’s just building. Almost anyone can do that. The next level of comfort is intellectual comfort. Does it make sense? Is it reasonable? Is this appropriate? Why did you do that? Why does the structure do this? Is that reasonable intellectually?

The third level of comfort is much more difficult. And that’s a spiritual comfort. Does it make you feel better? Does it make you happier? Does it change the way you live? We don’t just accommodate the way people live, we should improve it, we should enhance it. Without the three, I don’t think it’s really architecture. I don’t hear the word art spoken enough in architecture. It’s really important to understand that it’s an art form and we have to do more than just make a building stand up.

What work are you really proud of?

I think that Snowbird is probably the most important project I’ve done. Snowbird is basically a new village, a new idea, a new concept. The first modern American ski resort in the country, anywhere, actually. I would say that’s probably the most successful. But I think it’s also the most troublesome. I think that one can compromise certain things, but never compromise in principle.

Fifty years ago, the idea was to have a tram go up to a bridge, which is a megastructure, and do a bridge building that spans the entire canyon, and not have any cars. That was proposed because the canyon is very difficult, and we were snowed in all the time. Now, fifty years later, we’re struggling with endless cars, traffic jams, and the proposal of the gondola is hugely expensive.

Not getting people to understand the vision is hard. The plaza is the key part of Snowbird. I fought against the position of the Cliff Lodge because it was distant from the plaza, and because of the distance you had to get in the car. The idea was not to get in the car. I was disappointed to not see it fulfilled in its entirety. But yeah, I’m very proud of Snowbird, but I would like to have kept it tighter — less compromise.

What changes in architecture have you experienced in your career?

When I was just a kid, I met Frank Lloyd Wright; I must have been 17, 18 years old. I raised my hand. I said, “Mr. Wright, what do you do first?” He said, “Young man, I do it all at once.” Whoa, all at once. But that’s the truth.

I hear the notions that it is plan driven. It’s not plan driven if you can see the building while you’re drawing the plan. In the computer technology, they are not seeing the whole building. I think that’s a problem. But at the same time, we can’t live without the computer. I understand all the programs, how they all work, but I still draw. I think it’s about thinking first, it’s about the pencil drawing because it’s the most transparent between the mind and the hand. And then after that it’s making, and then after it is computing, it goes in a circle. And that notion actually is from Renzo Piano. That’s his notion about the circular motion of how one creates. So, you think, you draw, you make a model, you compute.

Right now, young people tend not to draw. They tend not to see the whole picture. They don’t visualize that because they’re too busy doing it and it’s not the same. That doesn’t mean to say it’s not important, but it’s important as well not to just think that the machine’s going to do it by itself.

Your advice for a young architect?

Don’t forget that architecture is an art form. I want to see the spiritual side. Certainly, the computer is important, but you’ve got to look at the computer as a tool. AI cannot take over. Certainly, it will help you, but I think that you really need to draw still. You need to think and never compromise your principles. I think art and architecture have to be both noun and verb. If we’re not doing the spiritual side or making something that’s going to make people happier or respond to it, then I don’t think it’s successful. I don’t want to see architecture as just a business. Certainly, we have to do that, but it’s also very important that it be considered an art form.

I like to think my teaching is not just teaching about architecture, but about life and about broader things: about integrity. People claim work that they didn’t do. That’s not acceptable. John Sugden said he had lunch with Philip Johnson. He went back to Mies van der Rohe’s office and he said, “Philip Johnson is claiming to have been the architect for the Seagram Building.” Mies just took a big, long drag on his cigar and said, “John, better Philip claims my work instead of the other way around.” Big statement.

It’s better to give credit to people who have done the work, than for them to simply assume that you’ve done something individually or to claim someone else’s work. That happens all too often. I think that truth is the most important principle I can think of.

I think work is actually a religion. A lot of people work to live. I live to work. That’s my life, and that’s why I still practice, and I’m still involved. That’s what I am. I’m an architect and that’s what makes me tick.

To watch the full interview, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N9koNRAEDiY.